Composition and source apportionment differences of daytime and nighttime samples of PM2.5 in the community of suburb in Tianjin during different heating periods

-

摘要:

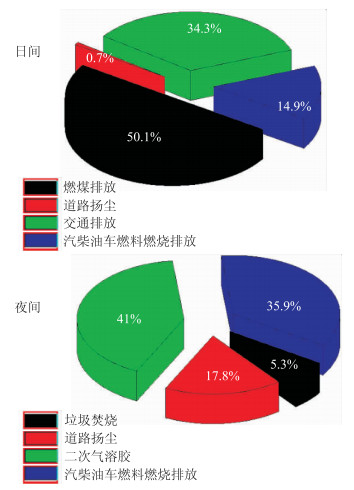

目的 了解在采暖和非采暖期天津市周边区域居民社区不同时段空气中细颗粒物(fine particulate matter,PM2.5)的污染和来源差异。 方法 采集市郊某社区2015-2016年间每日昼夜两时段的PM2.5样品,分别检测PM2.5样品的质量浓度,金属元素,多环芳烃和无机水溶性离子浓度,并运用正矩阵因子分解模型分析社区不同时段空气中PM2.5的金属元素,多环芳烃和无机水溶性离子的来源差异。 结果 在采暖期城市周边居民社区部分金属元素日间时段浓度高于夜间时段,在非采暖期部分多环芳烃和无机水溶性离子浓度夜间时段高于日间时段,而部分金属元素日间时段浓度高于夜间时段,采暖期城市周边居民社区空气PM2.5日间时段的主要来源为燃煤排放,来源贡献率为50.1%,夜间时段的主要来源分别为二次气溶胶和汽、柴油车燃料燃烧排放,来源贡献率分别为41.0%和35.9%。非采暖期城市周边居民社区空气PM2.5日间时段的主要来源为室内活动排放,夜间时段主要来源为二次气溶胶,来源贡献率分别为29.8%和31.1%。 结论 城市周边区域居民社区空气PM2.5的污染状况较为严重,不同采暖期和不同时段的污染来源均存在差异。 Abstract:Objective To study the pollution and source apportionment differences of different periods PM2.5 in the residential community of suburb in Tianjin City during heating and non-heating periods. Methods From 2015 to 2016, daytime and nighttime PM2.5 samples were collected at a community in the suburb of Tianjin. The mass concentration of PM2.5 samples and major chemical components in PM2.5, including metal elements, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and inorganic water-soluble ions were monitored. Positive matrix factorization (PMF) model was used to apportion potential sources of metal elements, PAHs and inorganic water-soluble ions in daytime and nighttime PM2.5. Results In the heating period, the concentrations of some metal elements of suburban residential community were higher in the daytime than in the nighttime. In the non-heating period, the concentrations of some PAHs and inorganic water-soluble ions of suburban residential community were higher in the nighttime than in the daytime. Meanwhile, the concentrations of some metal elements were greater in the daytime than in the nighttime. When in heating period, the main source of PM2.5 in the suburban residential community was coal combustion during daytime and its source contribution rate was 50.1% while secondary aerosol and fuel combustion emissions of gasoline and diesel vehicles were main sources during nighttime and their source contribution rates were 41.0% and 35.9%. The principal source of daytime PM2.5 in the suburban residential community was indoor activity emissions during non-heating period, and secondary aerosol was main source during nighttime and their source contribution rates were 29.8% and 31.1%. Conclusions The pollution status of PM2.5 in residential communities of suburban is serious, and the source apportionment of day and night PM2.5 samples has different in different heating periods. -

Key words:

- PM2.5 /

- Heating period /

- Source contribution rate /

- Positive matrix factorization /

- Period

-

表 1 不同采暖期天津市市郊昼夜PM2.5成分的浓度差异[M(P25,P75)]

Table 1. The difference of various components in day and night PM2.5 of suburban residential community in Tianjin under different heating periods [M(P25, P75)]

成分 采暖期 非采暖期 日间 夜间 Z值 P值 日间 夜间 Z值 P值 Phe (ng/m3) 0.73(0.28, 3.96) 0.63(0.28, 3.80) 0.22 0.823 0.28(0.28, 0.95) 0.28(0.28, 0.62) 0.21 0.835 Fl(ng/m3) 3.55(1.18, 14.25) 2.57(0.72, 12.20) 0.56 0.576 0.28(0.28, 4.17) 0.28(0.28, 3.68)b 2.12 0.034 Pyr(ng/m3) 3.27(1.03, 11.80) 2.36(0.68, 11.30) 0.45 0.653 0.40(0.20, 3.80) 0.43(0.20, 3.89) 1.19 0.234 BaA(ng/m3) 1.43(0.24, 9.73) 1.68(0.24, 10.99) 0.49 0.621 -a 0.24(0.24, 0.90)b 4.32 <0.001 BbF(ng/m3) 5.05(1.42, 21.90) 4.84(1.47, 24.00) 0.06 0.949 0.28(0.28, 1.01) 0.68(0.28, 4.98)b 4.19 <0.001 BkF(ng/m3) 1.46(0.66, 6.65) 1.21(0.41, 7.09) 0.27 0.787 0.24(0.24, 0.99) 0.24(0.24, 1.61)b 2.69 0.007 BaP(ng/m3) 1.34(0.28, 11.91) 1.74(0.28, 14.15) 0.38 0.705 -a 0.28(0.28, 1.53)b 4.32 <0.001 InP(ng/m3) 2.27(0.45, 12.40) 1.86(0.52, 12.35) 0.15 0.882 -a 0.26(0.26, 0.76)b 4.32 <0.001 DahA(ng/m3) 0.41(0.14, 3.15) 0.37(0.14, 2.87) 0.26 0.795 -a -a 0.00 1.000 BghiP(ng/m3) 2.27(0.71, 13.36) 1.62(0.92, 13.20) 0.31 0.758 0.26(0.26, 0.91) 0.44(0.26, 1.83)b 3.81 <0.001 Be(ng/m3) 0.02(0.01, 0.05)b 0.01(0.01, 0.02) 2.07 0.038 -a -a 0.00 1.000 Na(μg/m3) 0.01(0.01, 0.40) 0.01(0.01, 0.50) 0.41 0.679 0.13(0.01, 0.84)b 0.01(0.01, 1.99) 2.69 0.007 Mg(μg/m3) 0.05(0.00, 0.16) 0.04(0.00, 0.10) 0.78 0.437 0.22(0.00, 0.34)b 0.13(0.00, 2.02) 2.40 0.016 Al(μg/m3) 0.25(0.12, 0.40)b 0.11(0.06, 0.21) 2.60 0.009 0.23(0.02, 0.52)b 0.19(0.02, 0.40) 2.15 0.031 Ga(μg/m3) 0.28(0.03, 0.59) 0.24(0.01, 0.59) 0.32 0.751 1.13(0.01, 1.83)b 0.62(0.01, 5.87) 3.02 0.003 V(ng/m3) 3.47(1.66, 6.44) 2.34(0.74, 5.46) 1.45 0.147 7.43(0.03, 15.82)b 2.35(0.03, 10.94) 3.75 <0.001 Cr(ng/m3) 2.30(0.51, 4.26) 1.62(0.60, 3.61) 1.14 0.253 1.01(0.08, 15.04) 0.41(0.08, 6.86) 1.50 0.135 Ni(ng/m3) 3.10(1.83, 5.28) 2.38(1.24, 3.57) 1.85 0.065 2.84(0.05, 7.42)b 1.63(0.05, 5.07) 3.71 <0.001 Cu(μg/m3) 0.04(0.02, 0.07)b 0.02(0.01, 0.05) 2.52 0.012 0.02(0.00, 0.10) 0.01(0.00, 0.04) 1.41 0.157 Zn(μg/m3) 0.59(0.21, 0.80)b 0.28(0.08, 0.52) 2.55 0.011 0.15(0.04, 0.51) 0.11(0.00, 0.45) 0.96 0.338 As(μg/m3) 0.02(0.01, 0.03)b 0.01(0.01, 0.02) 2.55 0.011 6.04(1.91, 17.90) 4.27(0.09, 13.40) 1.50 0.133 Se(μg/m3) 0.01(0.01, 0.01)b 0.01(0.00, 0.01) 2.45 0.014 0.00(0.00, 0.01)b 0.00(0.00, 0.01) 3.31 0.001 Cd(ng/m3) 5.53(2.48, 7.66)b 2.27(1.06, 5.50) 2.60 0.009 0.71(0.01, 5.06) 0.89(0.01, 3.42) 0.68 0.495 Hg(ng/m3) 0.05(0.05, 0.08)b 0.05(0.05, 0.05) 2.48 0.013 -a -a 0.00 1.000 TI(ng/m3) 1.77(0.82, 2.81)b 1.18(0.49, 1.82) 2.67 0.007 0.24(0.01, 1.96) 0.41(0.01, 1.46) 0.22 0.828 Pb(μg/m3) 0.12(0.07, 0.16)b 0.07(0.04, 0.11) 2.89 0.004 0.04(0.01, 0.09) 0.04(0.00, 0.09) 1.56 0.119 Cl-(μg/m3) 4.92(2.03, 8.74) 5.18(2.01, 8.93) 0.12 0.903 0.39(0.01, 7.01) 1.60(0.70, 5.62)b 6.69 <0.001 SO42-(μg/m3) 20.80(11.17, 33.69) 16.70(6.93, 24.44) 1.52 0.129 11.06(0.01, 28.66) 11.06(4.83, 26.24) 0.39 0.694 NO3-(μg/m3) 25.30(12.60, 44.95) 16.70(7.31, 36.01) 1.26 0.207 2.79(0.01, 18.66) 10.66(2.84, 19.63)b 5.29 <0.001 NH4+(μg/m3) 21.20(9.50, 28.00) 13.40(5.31, 23.36) 1.42 0.156 1.42(0.04, 20.38) 8.35(0.04, 14.03)b 2.60 0.009 注:a表示该成分浓度数值为常量;b表示昼夜浓度比较差异有统计学意义,P < 0.05。 -

[1] Kloog I, Ridgway B, Koutrakis P, et al. Long- and short-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality: using novel exposure models[J]. Epidemiology, 2013, 24(4): 555-561. DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318294beaa. [2] 张经纬, 冯利红, 侯常春, 等. 天津市大气污染对儿童呼吸系统疾病影响的病例交叉研究[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2019, 23(5): 545-549. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2019.05.011.Zhang JW, Feng LH, Hou CC, et al. The impact of air pollution on children's respiratory disease in Tianjin: a case over study[J]. Chin J Dis Control Prev, 2019, 23(5): 545-549. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2019.05.011. [3] 李恩平. 天津市三个层面区域经济关系及优化对策研究[J]. 天津商业大学学报, 2017, 37(1): 38-44. DOI: 1674-2362(2017)01-0038-07.Li EP. Regional economic relations and optimization countermeasures at three levels in Tianjin metropolitan area[J]. Journal of Tianjin University of Commerce, 2017, 37(1): 38-44. DOI: 1674-2362(2017)01-0038-07. [4] Norris G, Duvall R, Brown S, et al. EPA positive matrix factorization (PMF 5.0) fundamentals and user guide[R]. Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2014. [5] Paatero P, Tapper U. Analysis of different modes of factor analysis as least squares fit problem[J]. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 1993, 18(2): 183-194. DOI: 10.1016/0169-7439(93)80055-M. [6] Bragato M, Joshi K, Carlson JB, et al. Combustion of coal, bagasse and blends thereof: Part Ⅱ: Speciation of PAH emission[J]. Fuel, 2012, 96(6): 51-58. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2011.11.069. [7] Birmili W, Allen AG, Bary F, et al. Trace metal concentrations and water solubility in size-fractionated atmospheric particles and influence of road traffic[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2006, 40(4): 1144-1153. DOI: 10.1021/es0486925. [8] Yao XH, Chan CK, Fang M, et al. The water-soluble ionic composition of PM2.5 in Shanghai and Beijing, China[J]. Atmos Environ, 2002, 36(26): 4223-4234. DOI: 10.1016/s1352-2310(02)00342-4. [9] Xie Y, Zhao B. Chemical composition of outdoor and indoor PM2.5 collected during haze events: transformations and modified source contributions resulting from outdoor-to-indoor transport[J]. Indoor Air, 2018, 28(6): 828-839. DOI: 10.1111/ina.12503. [10] Yu L, Wang G, Zhang R, et al. Characterization and source apportionment of PM2.5 in an urban environment in Beijing[J]. Aerosol Air Qual Res, 2013, 13(2): 574-583. DOI: 10.4209/aaqr.2012.07.0192. [11] Hagler GS, Bergin MH, Salmon LG, et al. Source areas and chemical composition of fine particulate matter in the Pearl River Delta region of China[J]. Atmos Environ, 2006, 40(20): 3802-3815. DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.02.032. [12] Zhang J, Zhou X, Wang Z, et al. Trace elements in PM2.5 in Shandong province: source identification and health risk assessment[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2017, 621(8): 558-577. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.292. [13] Chin JY, Batterman SA, Northrop WF, et al. Gaseous and particulate emissions from diesel engines at idle and under load: comparison of biodiesel blend and ultralow sulfur diesel fuels[J]. Energy Fuels, 2012, 26(11): 6737-6748. DOI: 10.1021/ef300421h. [14] Guarieiro ALN, JSantos VS, Eiguren-Fernandez A, et al. Redox activity and PAH content in size-classified nanoparticles emitted by a diesel engine fuelled with biodiesel and diesel blends[J]. Fuel, 2014, 116(2): 490-497. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.08.029. [15] Liao HT, Chou CC, Chow JC, et al. Source and risk apportionment of selected VOCs and PM2.5 species using partially constrained receptor models with multiple time resolution data[J]. Environ Pollut, 2015, 205(10): 121-130. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.05.035. [16] Yang Y, Liu L, Xu C, et al. Source apportionment and influencing factor analysis of residential indoor PM2.5 in Beijing[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018, 15(4): 686-704. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph15040686. [17] Turap Y, Talifu D, Wang X, et al. Concentration characteristics, source apportionment, and oxidative damage of PM2.5-bound PAHs in petrochemical region in Xinjiang, NW China[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2018, 25(23): 22629-22640. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-018-2082-3. -

下载:

下载: