Association between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and congenital heart disease in offspring based on a case-control study

-

摘要:

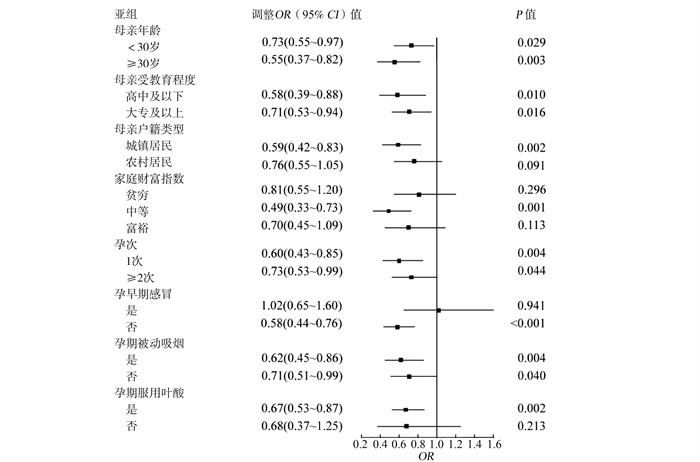

目的 探讨母亲孕期铁营养与子代先天性心脏病(congenital heart disease,CHD)的关系。 方法 数据来源于陕西省2014年1月―2016年12月开展的CHD病例对照研究,对纳入孕妇进行膳食营养问卷调查。采用条件logistic回归分析模型分析母亲孕期铁营养与子代CHD及其各亚型的关系,并进行亚组分析探索其稳定性。 结果 在调整了混杂因素后,母亲孕期增补铁剂降低了子代CHD的发生风险(< 30 d:OR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.37~0.79;≥30 d:OR=0.25, 95% CI: 0.16~0.38),孕期膳食铁摄入量较高(≥29 mg/d)降低了子代CHD的发生风险(OR=0.69, 95% CI: 0.54~0.88),亚组分析结果显示,母亲孕期铁营养和子代CHD的关系稳定。此外,母亲孕期增补铁剂≥30 d子代在室间隔缺损(ventricular septal defect, VSD)、房间隔缺损(atrial septal defect, ASD)、动脉导管未闭(patent ductus arteriosus, PDA)、法洛四联症(tetralogy of fallot, TOF)上发生风险均降低,增补铁剂 < 30 d子代在ASD发生风险降低,孕期膳食铁摄入量较高(≥29 mg/d)子代在VSD、PDA发生风险均降低。 结论 母亲孕期铁营养水平升高降低了子代CHD的发生风险,孕妇孕期应注意机体铁营养的摄入和补充,促进母婴健康。 Abstract:Objective The study aims to explore the relationship between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and congenital heart disease (CHD) in offspring. Methods A matched case-control study was conducted in Shaanxi Province from January 2014 to December 2016, and a food frequency questionnaire was used to collect dietary nutrition during pregnancy among women. The conditional logistic regression model was adopted to examine the association between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and CHD and its subtypes in offsprings, and subgroup analysis was further performed to test results stability. Results After adjusting for confounding factors, maternal iron supplementation during pregnancy reduced the risk for CHD in offsprings (< 30 days: OR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.37-0.79; ≥ 30 days: OR=0.25, 95% CI: 0.16-0.38). Higher dietary iron intake during pregnancy (≥29mg/d) reduced the risk for CHD in offsprings (OR=0.69, 95% CI: 0.54-0.88). The subgroup analysis showed that the relationship between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and CHD was stable. In addition, the risk of ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and tetralogy of fallot (TOF) in the offspring was lower among mothers with iron supplementation ≥30 days during pregnancy. If the mothers supplemented iron less than 30 days, the risk for ASD in the offspring would reduce. The risk of VSD and PDA in the offspring was lower among mothers with a higher dietary iron intake during pregnancy (≥29mg/d). Conclusions The higher iron nutrition level of mothers during pregnancy is associated with the reduced risk for CHD in offspring. Pregnant women should ensure adequate iron intake during pregnancy to promote the health of mothers and babies. -

Key words:

- Iron nutrition /

- Congenital heart disease /

- Pregnancy /

- Case-control study

-

表 1 研究对象一般资料[n(%)]

Table 1. General information of subjects [n(%)]

指标 病例组(n=600) 对照组(n=1 200) χ2值 P值 指标 病例组(n=600) 对照组(n=1 200) χ2值 P值 母亲年龄(岁) 3.085 0.079 孕早期感冒 22.227 < 0.001 < 30岁 378(63.00) 806(67.17) 是 185(30.83) 249(20.75) ≥30岁 222(37.00) 394(32.83) 否 415(69.17) 951(79.25) 母亲民族 10.658 0.001 孕早期发烧 3.161 0.075 汉族 585(97.50) 1 192(99.33) 是 54(9.00) 80(6.67) 少数民族 15(2.50) 8(0.67) 否 546(91.00) 1 120(93.33) 母亲受教育程度 88.615 < 0.001 孕期饮酒 15.298 < 0.001 高中及以下 264(44.00) 270(22.50) 是 18(3.00) 8(0.67) 大专及以上 336(56.00) 930(77.50) 否 582(97.00) 1 192(99.33) 母亲户籍类型 178.249 < 0.001 孕期被动吸烟 36.090 < 0.001 城镇居民 201(33.50) 800(66.67) 是 345(57.50) 510(42.50) 农村居民 399(66.50) 400(33.33) 否 255(42.50) 690(57.50) 家庭财富指数 116.335 < 0.001 孕期染烫头发 13.292 < 0.001 贫穷 313(52.17) 331(27.58) 是 37(6.17) 32(2.67) 中等 167(27.83) 398(33.17) 否 563(93.83) 1 168(97.33) 富裕 120(20.00) 471(39.25) 孕期服用叶酸 21.160 < 0.001 孕次 24.396 < 0.001 是 476(79.33) 1 051(87.58) 1次 236(39.33) 620(51.67) 否 124(20.67) 149(12.42) ≥2次 364(60.67) 580(48.33) 表 2 母亲孕期铁营养与子代CHD关系的logistic回归分析

Table 2. Logistic regression analysis of the relationship between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and CHD in offspring

指标 病例[n(%)] 对照[n(%)] 模型1 模型2 模型3 OR (95% CI)值, P值 调整OR (95% CI)值a, P值 调整OR (95% CI)值b, P值 孕期铁剂增补 否 520(86.67) 774(64.50) 1.00 1.00 1.00 增补 < 30 d 48(8.00) 176(14.67) 0.41(0.29~0.58), < 0.001 0.53(0.36~0.76), 0.001 0.54(0.37~0.79), 0.001 增补≥30 d 32(5.33) 250(20.83) 0.20(0.13~0.29), < 0.001 0.23(0.15~0.34), < 0.001 0.25(0.16~0.38), < 0.001 孕期膳食铁摄入 < 29 mg/d 434(72.33) 721(60.08) 1.00 1.00 1.00 ≥29 mg/d 166(27.67) 479(39.92) 0.57(0.45~0.70), < 0.001 0.65(0.51~0.82), < 0.001 0.69(0.54~0.88), 0.003 注:a调整了母亲民族、母亲受教育程度、母亲户籍类型、家庭财富指数、孕次;b调整所有基线协变量(母亲民族、母亲受教育程度、母亲户籍类型、家庭财富指数、孕次、孕早期感冒、孕期饮酒、孕期被动吸烟、孕期染烫头发、孕期服用叶酸)。 表 3 母亲孕期铁营养与子代CHD关系的疾病异质性分析

Table 3. Disease heterogeneity analysis of the relationship between maternal iron nutrition during pregnancy and CHD in offspring

指标 VSD(n=187) 调整OR (95% CI)值 ASD(n=75) 调整OR (95% CI)值 PDA(n=75) 调整OR (95% CI)值 AVSD(n=51) 调整OR (95% CI)值 TOF(n=45) 调整OR (95% CI)值 孕期铁剂增补 否 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 增补 < 30 d 0.59(0.30~1.16) 0.26(0.07~0.91) 0.57(0.23~1.40) 0.61(0.18~2.06) 0.11(0.01~1.78) 增补≥30 d 0.20(0.09~0.44) 0.25(0.08~0.74) 0.22(0.06~0.82) 0.82(0.20~3.31) 0.14(0.02~0.79) 孕期膳食铁摄入 < 29 mg/d 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 ≥29 mg/d 0.63(0.40~0.99) 0.77(0.36~1.65) 0.47(0.23~0.95) 0.70(0.30~1.67) 0.66(0.20~2.18) 注: 调整了母亲民族、母亲受教育程度、母亲户籍类型、家庭财富指数、孕次。 -

[1] Li W, Bing L, Jianhong X, et al. Prevalence of congenital heart defect in Guangdong province, 2008-2012[J]. BioMed Central, 2014, 14: 152. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-152. [2] Vander LD, Konings EEM, Slager MA, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011, 58(21): 2241-2247. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. [3] Qu Y, Liu X, Zhuang J, et al. Incidence of congenital heart disease: the 9-year experience of the Guangdong registry of congenital heart disease, China. [J]. PloS one, 2016, 11(7): e0159257. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159257.eCollection2016. [4] 李文先, 杜莉, 李旻明, 等. 2016―2018年上海市不同监测时段出生缺陷发病率比较[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2021, 25(10): 1226-1230. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2021.10.020.Li WX, Du L, Li MM, et al. Comparison of the incidence of birth defects in Shanghai during different surveillance periods from 2016 to 2018[J]. Chin J Dis Control Perv, 2021, 25(10): 1226-1230. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2021.10.020. [5] Adriana D, Christine AL, Jack LP, et al. The iron exporter ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis[J]. Cell Metab, 2005, 1(3): 191-200. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.003. [6] Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Yang W, et al. Periconceptional nutrient intakes and risks of conotruncal heart defects[J]. Birth Defects Res A, 2010, 88(3): 144-151. DOI: 10.1002/bdra.20648. [7] Yang J, Kang Y, Cheng Y, et al. Iron intake and iron status during pregnancy and risk of congenital heart defects: A case-control study. [J]. Inter J cardiol, 2020, 301: 74-79. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.11.115. [8] 杨姣梅. 孕期营养和铁代谢相关基因多态性与先天性心脏病的关联研究[D]. 西安: 西安交通大学, 2018.Yang JM. Association study of genetic polymorphisms related to nutrition and iron metabolism during pregnancy and congenital heart disease[D]. Xi'an: Xi'an Jiaotong University, 2018. [9] 杨月欣. 中国食物成分表2004[M]. 北京: 北京大学医学出版社, 2005: 3-120.Yang YX. Chinese Food Composition Table 2004[M]. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press, 2005: 3-120. [10] 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会. 587.3-2017 WT中国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量. 第3部分: 微量元素[S]. 北京: 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会, 2017: 1-4.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 587.3-2017 WT Chinese Residents' Dietary Nutrient Reference Intakes. Part 3: Trace Elements[S]. Beijing: National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2017: 1-4. [11] Nicoll R. Environmental contaminants and congenital heart defects: a re-evaluation of the evidence[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018, 15(10): 2096. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph15102096. [12] 陈晓媛, 王安辉, 苏海砾. 1 009例婴幼儿先天性心脏病危险因素的病例对照研究[J]. 中华疾病控制杂志, 2016, 20(11): 1114-1116. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2016.11.009.Chen XY, Wang AH, Su HS. A case-control study of risk factors for congenital heart disease in 1 009 infants and children[J]. Chin J Dis Control Perv, 2016, 20(11): 1114-1116. DOI: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2016.11.009. [13] 鞠叶兰, 王晨虹, 程黎, 等. 孕期微量元素对先天性心脏病的影响[J]. 中国现代医学杂志, 2016, 26(1): 57-61. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2016.01.011.Ju YL, Wang CH, Cheng L, et al. The influence of trace elements during pregnancy on congenital heart disease[J]. China J Mod Med, 2016, 26(1): 57-61. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2016.01.011. [14] Yu F, Jun C, Xing T, et al. Non-inheritable risk factors during pregnancy for congenital heart defects in offspring: A matched case-control study[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2018, 264 : 45-52. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.003. [15] Kathy JJ, Adolfo C, Jeffrey AF, et al. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the american heart association council on cardiovascular disease in the young[J]. Circulation, 2007, 115(23): 2995-3014. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183216. [16] Anne MM, Caitriona NE, Divyanshu J, et al. Is low iron status a risk factor for neural tube defects?[J]. Birth Defect Res A, 2014, 100(2): 100-106. DOI: 10.1002/bdra.23223. [17] Allen LH. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2000, 71(5 Suppl): 1280S-1284S. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1280s. [18] O'Connor DL. Interaction of iron and folate during reproduction. [J]. Prog Food Nutr Sci, 1991, 15(4): 231-254. [19] 刘海虹, 李雪兰, 王磊清, 等. 陕西地区妊娠期妇女铁缺乏和缺铁性贫血患病率调查研究[J]. 陕西医学杂志, 2018, 47(7): 943-946. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7377.2018.07.040.Liu HH, Li XL, Wang LQ, et al. Investigation on the prevalence of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in Shaanxi Province[J]. Shanxi Med J, 2018, 47(7): 943-946. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7377.2018.07.040. [20] Jaclyn LFB, Marilyn T, Logan GS, et al. Reproducibility of reported nutrient intake and supplement use during a past pregnancy: a report from the Children's Oncology Group[J]. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 2010, 24(1): 93-101. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01070.x. [21] Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Godfrey KM, et al. Women's dietary patterns change little from before to during pregnancy[J]. J Nutr, 2009, 139(10): 1956-1963. DOI: 10.3945/jn.109.109579. -

下载:

下载: