Associations between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and human papillomavirus infection in women with abnormal cervical cytology

-

摘要:

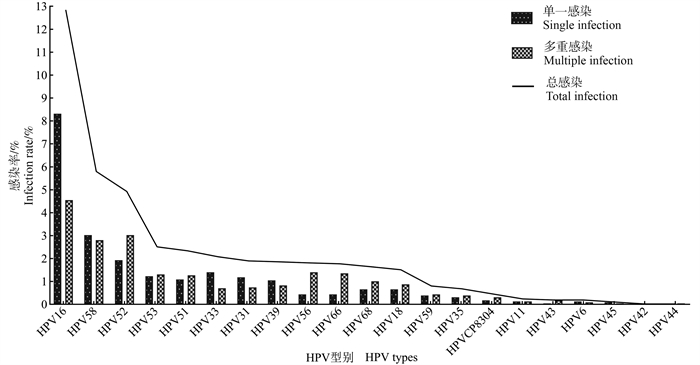

目的 探讨宫颈细胞学异常妇女多环芳烃(polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, PAHs)暴露与人乳头瘤病毒(human papillomavirus, HPV)感染的关系。 方法 选取课题组建立的自然人群队列中宫颈细胞学异常的2 285名妇女为研究对象, 利用队列基线资料进行横断面研究。在收集研究对象基线资料的同时, 进行宫颈脱落细胞HPV分型检测和尿液1-羟基芘(1-hydropyrene, 1-OHP)浓度的测定, 分析PAHs暴露与HPV感染的关系。 结果 宫颈细胞学异常妇女HPV感染率为32.3%, 其中单一和多重感染率分别为22.8%和9.4%, 高危型人乳头瘤病毒(high-risk human papillomavirus, HR-HPV)感染率为31.6%, 居前5位的感染型别为HPV16、HPV58、HPV52、HPV53和HPV51。HPV及其单一/多重、HR-HPV、HPV16、HPV58、HPV52、HPV53和HPV51感染的妇女, PAHs的暴露水平均高于未感染者(均P < 0.001), PAHs高暴露均可增加各类型HPV的感染风险, 且随着PAHs暴露水平的升高, HPV及其单一/多重, HR-HPV, HPV16、HPV58、HPV52、HPV53和HPV51感染的风险均呈上升趋势(均P < 0.05)。进一步经分层分析发现, 在35~ < 45岁、初中及以下文化程度、被动吸烟、未绝经和产次≥3次的妇女中, PAHs高暴露发生HPV和HPV16感染的风险更大。 结论 PAHs高暴露可增加宫颈细胞异常的妇女HPV及高危型HPV的感染风险, 尤其是35~ < 45岁、文化程度较低、被动吸烟、未绝经和多产次的妇女感染风险更大。 Abstract:Objective This study aimed to explore the association between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) exposure and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in women with abnormal cervical cytology. Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted on a cohort of 2 285 women with abnormal cervical cytology.The cohort was previously established by our research group.The study analyzed the association between PAHs and HPV infection, using HPV infection status in cervical exfoliated cells and 1-hydroxypyrene (1-OHP) exposure levels in urine detected at the same time. Results In women with abnormal cervical cytology, the HPV infection rate was 32.3%, with single and multiple infection rates of 22.8% and 9.4%, respectively.The infection rate of high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) was 31.6%, and the top five infection types were HPV16, HPV58, HPV52, HPV53, and HPV51.The exposure levels of PAHs in women infected with HPV and its single or multiple, HR-HPV, HPV16, HPV58, HPV52, HPV53, and HPV51 were all higher than those without infection (all P < 0.001).High exposure to PAHs could increase the risk of infection of the above types of HPV, showing a dose-response relationship between PAHs exposure levels and the risk of HPV infection (all P < 0.05).Further stratified analysis showed that among women aged 35- < 45 years, with junior high school education level or below, passive smoking, premenopausal women and parities ≥3 times, the risk of HPV infection and high-risk HPV16 infection was greater in those with high PAHs exposure. Conclusions High exposure to PAHs could increase the risk of HPV or high-risk HPV infection in women with cervical cell abnormalities, especially in women aged 35- < 45 years, with low education level, passive smoking, multiple parturition, and premenopausal women. -

图 2 不同HPV感染状态下的PAHs暴露水平

1. 1-OHP:1-羟基芘;2. HPV:人乳头瘤病毒;3. A、B、C、D、E、F、G、H、I分别为HPV、HPV单一、HPV多重、HR-HPV、HPV16、HPV58、HPV52、HPV53、HPV51感染状态下1-OHP的暴露水平;4. a:P < 0.05。

Figure 2. Exposure levels of PAHs in different HPV infection states

1. 1-OHP: 1-hydropyrene; 2. HPV: human papillomavirus; 3. A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I were exposure levels of 1-OHP in HPV, HPV single, HPV multiple, HR-HPV, HPV16, HPV58, HPV52, HPV53, HPV51 infection states, respectively; 4. a: P < 0.05.

图 3 PAHs不同暴露等级与HPV感染的剂量-反应关系

1. PAHs: 多环芳烃;2. Q1为 < 0.06 μmol/molCr;3. Q2为0.06~0.07 μmol/molCr;4. Q3为0.08~0.11 μmol/molCr;5. Q4为>0.11 μmol/molCr;6. aOR值为对年龄、文化程度、被动吸烟、绝经和产次调整后的OR值。

Figure 3. Dose-response relationship between PAHs exposure and HPV infection

1. PAHs: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; 2. Q1: < 0.06 μmol/molCr; 3. Q2:0.06-0.07 μmol/molCr; 4. Q3:0.08-0.11 μmol/molCr; 5. Q4:>0.11 μmol/molCr; 6. aOR values were adjusted for age, education, passive smoking, menopause and parturition.

表 1 PAHs暴露与HPV感染的关系分析

Table 1. Relationship between PAHs exposure and HPV infection and its different types

感染状态

Infection statusPAHs 人数(占比/%)

Number of people (proportion/%)χ2值

χ2 valueP值

P valueOR值(95% CI)

OR value(95% CI)aOR值(95% CI)①

aOR value(95% CI)①HPV感染

HPV infection低暴露

Low exposure312(22.00) 179.73 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure425(49.00) 3.41(2.84~4.09) 3.14(2.60~3.78) HPV单一感染

HPV single infection低暴露

Low exposure240(16.90) 74.29 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure282(32.50) 2.37(1.94~2.89) 2.17(1.78~2.66) HPV多重感染

HPV multiple infection低暴露

Low exposure72(5.10) 83.26 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure143(16.50) 3.69(2.74~4.97) 3.36(2.49~4.55) HR-HPV感染

HR-HPV infection低暴露

Low exposure309(21.80) 166.27 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure413(47.60) 3.27(2.72~3.92) 3.00(2.48~3.61) HPV16感染

HPV16 infection低暴露

Low exposure102(7.20) 107.29 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure192(22.10) 3.67(2.84~4.75) 3.25(2.50~4.23) HPV58感染

HPV58 infection低暴露

Low exposure60(4.20) 17.22 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure73(8.40) 2.08(1.46~2.96) 1.92(1.35~2.75) HPV52感染

HPV52 infection低暴露

Low exposure49(3.50) 17.64 < 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure64(7.40) 2.23(1.52~3.26) 2.10(1.42~3.09) HPV53感染

HPV53 infection低暴露

Low exposure24(1.70) 10.81 0.001 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure34(3.90) 2.37(1.40~4.03) 2.32(1.35~3.97) HPV51感染

HPV51 infection低暴露

Low exposure23(1.60) 8.90 0.003 1.00 1.00 高暴露

High exposure31(3.60) 2.25(1.30~3.88) 2.13(1.22~3.70) 注:PAHs,多环芳烃。

① aOR值为对年龄、文化程度、被动吸烟、绝经和产次调整后的OR值。

Note:PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

① aOR values were adjusted for age, education, passive smoking, menopause and parturition. -

[1] Ifegwu OC, Anyakora C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: part Ⅱ, urine markers[J]. Adv Clin Chem, 2016, 75: 159-183. DOI: 10.1016/bs.acc.2016.03.001. [2] Wentzensen N, Clarke MA. Cervical cancer screening-past, present, and future[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2021, 30(3): 432-434. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1628. [3] Alam S, Conway MJ, Chen HS, et al. The cigarette smoke carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene enhances human papillomavirus synthesis[J]. J Virol, 2008, 82(2): 1053-1058. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01813-07. [4] Maher DM, Bell MC, O'Donnell EA, et al. Curcumin suppresses human papillomavirus oncoproteins, restores p53, Rb, and PTPN13 proteins and inhibits benzo[a]pyrene-induced upregulation of HPV E7[J]. Mol Carcinog, 2011, 50(1): 47-57. DOI: 10.1002/mc.20695. [5] Alam S, Bowser BS, Conway MJ, et al. Downregulation of Cdc2/CDK1 kinase activity induces the synthesis of noninfectious human papillomavirus type 31b virions in organotypic tissues exposed to benzo[a]pyrene[J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(9): 4630-4645. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.02431-09. [6] Cheng YW, Lin FC, Chen CY, et al. Environmental exposure and HPV infection may act synergistically to induce lung tumorigenesis in nonsmokers[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(15): 19850-19862. DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.7628. [7] Li X, Ding L, Song L, et al. Effects of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons combined with high-risk human papillomavirus infection on cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a population study in Shanxi Province, China[J]. Int J Cancer, 2020, 146(9): 2406-2412. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.32562. [8] Yu YQ, Jiang MY, Dang L, et al. Changes in high-risk HPV infection prevalence and associated factors in selected rural areas of China: a multicenter population-based study[J]. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022, 9: 911367. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2022.911367. [9] Song L, Lyu Y, Ding L, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in women with abnormal cervical cytology: a population-based study in Shanxi Province, China[J]. Cancer Manag Res, 2020, 12: 12583-12591. DOI: 10.2147/CMAR.S269050. [10] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21660. [11] Ji F, Wuerkenbieke D, He Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR: an oncogene in human cervical cancer interacting with microRNA-17-5p[J]. Oncol Res, 2018, 26(3): 353-361. DOI: 10.3727/096504017X15002869385155. [12] Bao YP, Li N, Smith JS, et al. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in the cervix of Chinese women: a meta-analysis[J]. Int J STD AIDS, 2008, 19(2): 106-111. DOI: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007113. [13] de Sanjosé S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2007, 7(7): 453-459. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5. [14] Zhao FH, Lewkowitz AK, Hu SY, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in China: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based studies[J]. Int J Cancer, 2012, 131(12): 2929-2938. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.27571. [15] Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115, 789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer[J]. Int J Cancer, 2012, 131(10): 2349-2359. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [16] de Sanjosé S, Serrano B, Castellsagué X, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and related cancers in the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) countries. A WHO/ICO HPV information centre report[J]. Vaccine, 2012, 30(Suppl 4): D1-83, ⅵ. DOI: 10.1016/S0264-410X(12)01435-1. [17] Boström CE, Gerde P, Hamberg A, et al. Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2002, 110(Suppl 3): 451-488. DOI: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241197. [18] Bowser BS, Alam S, Meyers C. Treatment of a human papillomavirus type 31b-positive cell line with benzo[a]pyrene increases viral titer through activation of the Erk1/2 signaling pathway[J]. J Virol, 2011, 85(10): 4982-4992. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.00133-11. [19] Mehta H, Nazzal K, Sadikot RT. Cigarette smoking and innate immunity[J]. Inflamm Res, 2008, 57(11): 497-503. DOI: 10.1007/s00011-008-8078-6. [20] Schabath MB, Villa L, Lin HY, et al. A prospective analysis of smoking and human papillomavirus infection among men in the HPV in men study[J]. Int J Cancer, 2014, 134(10): 2448-2457. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.28567. [21] Kelsey KT, Nelson HH, Kim S, et al. Human papillomavirus serology and tobacco smoking in a community control group[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2015, 15: 8. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-014-0737-3. [22] Hirose T, Morito K, Kizu R, et al. Estrogenic/antiestrogenic activities of benzo[a]pyrene monohydroxy derivatives[J]. J Health Sci, 2001, 47(6): 532-558. DOI: 10.1248/jhs.47.552. [23] Attanasio R, Gust DA, Wilson ME, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of estrogen and progesterone replacement in a nonhuman primate model[J]. J Clin Immunol, 2002, 22(5): 263-269. DOI: 10.1023/A:1019997821064. [24] Enomoto LM, Kloberdanz KJ, Mack DG, et al. Ex vivo effect of estrogen and progesterone compared with dexamethasone on cell-mediated immunity of HIV-infected and uninfected subjects[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2007, 45(2): 137-143. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180471bae. -

下载:

下载: