Systematic review of association between metabolic syndrome and its components with neurocognitive impairment among HIV-infected population

-

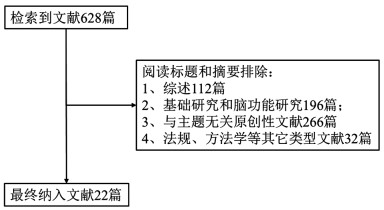

摘要: 为了解人类免疫缺陷病毒(human immunodeficiency virus, HIV)感染者代谢综合征(metabolic syndrome, MS)与神经认知损伤关联研究现状,系统检索Ovid Medline、Embase、中国知网、维普中文期刊服务平台、万方数据知识服务平台等数据库1992-2019年间发表的关于HIV感染者MS与神经认知损伤关联的原创性研究文献并对符合纳入排除标准文献进行分析归纳总结。最终共纳入22篇文献,包括14篇横断面研究、7篇队列研究和1篇二手资料分析;其中10篇研究纳入了HIV阴性人群对照。根据量表评估神经认知损伤程度,指标主要为测试分数。综述结果显示,HIV感染者代谢紊乱较普遍,神经认知损伤患病率存在较大的地区差异;HIV感染者MS与神经认知损伤风险增加相关。由于各研究采用不同量表对神经认知及单个功能领域损伤进行评估,不同研究中MS组分与神经认知及各功能领域之间关联复杂,不同功能领域结果甚至存在较大差异。HIV感染者代谢紊乱可能与神经认知功能不同领域损伤风险增加有关。鉴于目前研究证据有限且主要集中在欧美发达国家,需要更多其它地区及发展中国家的研究证据。Abstract: To systematically review the literature about the association between metabolic syndrome (MS) and neurocognitive impairments (NCIs) among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients. We systematically searched and reviewed related literature published on databases of Ovid Medline, Embase, CNKI, CQVIP and Wanfang Data from 1992 to 2019. Information excerpted from papers that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were analyzed. A total of 22 articles were included, including 14 cross-sectional studies, seven cohort studies and one secondary analysis, which were mainly conducted in the United States. HIV-negative controls were included in ten studies. NCIs were assessed by using neuropsychological battery. Metabolic disturbance was prevalent and NCIs was also prevalent with obvious heterogeneity across different geographic areas. Summarized results suggested that MS was associated with increased risk of NCIs. In consideration of different scales applied in different studies for the neurocognitive assessment and related ability domains, the relationship between MS components and NCIs and/or ability domains was found to be complicated. Some of these studies revealed distinct differences in ability domains evaluation. Metabolic disturbance may increase risks of various aspects of NCIs in HIV patients. In view of the limited evidence, more research is needed in other regions and developing countries.

-

表 1 22篇纳入文献基本情况

Table 1. Characteristic of 22 included studies

发表时间 研究类型 研究现场 研究时间 样本来源 ART (%) 样本量 结局指标 功能领域数 患病率 文献质量评分 HIV+ 对照 2005[3] 横断面研究 美国 2001.10-2003.11 HAHC 73.4 199 HAD, MCMD 6 19 2006[4] 横断面研究 美国 2001.10-2005.6 HAHC 73.1 145 正常, MCMD, HAD 7 0.7% MCMD, 0.7% HAD 20 2009[5] 横断面研究 美国 2004.7-2006.1 MACS 428 207 受损,正常 4 18 2010[6] 横断面研究 北美, 巴西, 澳大利亚, 泰国 2005.7-2006.1 SMART 92.5 292 NCI, 校正分数 1 14.0% 18 2011[7] 横断面研究 美国 2006.6-2007.9 WIHS 983 467 未校正分数 2 20 2012[8] 横断面研究 美国 2006.6-2007.9 CHARTER 82.3 130 NCI 7 40% 19 2013[9] 横断面研究 意大利 2010.7-2010.10 两个临床中心 93.9 245 校正分数 6 20 2013[10] 横断面研究 美国 2004.10-2008.9 WIHS 1 196 494 未校正分数 4 19 2015[11] 横断面研究 美国 2003.9-2007.8 CHARTER 99.0 152 NCI, HAND, 校正分数 7 28% NCI 20 2015[12] 队列研究 法国 2007.6-2009.11招募 医院为基础的队列 95.0 400 正常, ANI, MND, HAD 6 20.8% ANI, 31.0% MND, 6.7% HAD 19 2015[13] 横断面研究 美国 2009.4-2011.4 WIHS 659 335 校正分数 6 20 2016[14] 队列研究 美国 1996.1-2010.12 MACS 100.0 273 516 校正分数 5 21 2016[15] 队列研究 美国 2007-2012 MACS 364 正常, HAND (ANI, MND, HAD) 6 33.0% (14% ANI, 14% MND, 5% HAD) 19 2016[16] 队列研究 荷兰 2011.12-2013.8 AGE hIV 20.0 103 74(模型校正) MNC分数和二分类结果 6 17% 20 2017[17] 横断面研究 美国 2007-2010 医院为基础研究 86.7 90 校正分数 7 20 2018[18] 队列研究 美国 1999.4-2016.10 MACS 100.0 900 1149 校正分数 5 20 2018[19] 横断面研究 巴西 2013.5-2015.2 医院为基础研究 412 正常, ANI, MND, HAD 6 50.9%ANI, 16.2% MND, 6.3% HAD 20 2019[20] 二次分析 中国, 印度, 尼日利亚 三个国家时间不同 医院、社区均有 761 NCI, 校正分数 7 27.7% 16 2019[21] 队列面研究 美国 2006.6-2007.9 CHARTER; MACS 100.0 47;72 NCI, 校正分数 7 48.9%下降 18 2019[22] 横断面研究 美国 2013.5-2016.1 MDSA 95.4 109 92 校正分数 7 21 2019[23] 横断面研究 美国 SASH, MDSA 97.2 144 102 神经认知紊乱, 校正分数 7 15.9% 17 2019[24] 队列研究 美国 1996后 MACS 316 656 校正分数 6 21 注:ART:抗逆转录病毒治疗;HAD:HIV相关性痴呆(HIV-associated dementia, HAD);MCMD:轻微认知运动障碍(minor cognitive motor disorder, MCMD);NCI:神经认知损伤(neurocognitive impairment, NCI);ANI:无症状神经认知损伤(asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment, ANI);MND:轻微神经认知障碍(mild neurocognitive disorder, MND);MNC:多元规范比较(multivariate normative comparison, MNC);CHARTER:HIV抗逆转录病毒治疗中枢神经系统影响的研究(CNS HIV anti-retroviral therapy effects research, CHARTER);HAHC:夏威夷衰老与HIV队列研究(Hawaii aging with HIV cohort study, HAHC);SMART:抗逆转录病毒疗法的管理策略(the strategies for management of antiretroviral therapy, SMART);WIHS:多机构HIV妇女研究(women's interagency HIV study, WIHS);MACS:多中心HIV队列研究(multicenter AIDS cohort study, MACS);AGE hIV:队列研究名称,致力于研究HIV人群衰老及其相关疾病。SASH:老年HIV感染者寿命研究(successfully aging seniors with HIV, SASH);MDSA:多维度衰老与寿命研究(multi-dimensional successful aging, MDSA)。 表 2 HIV感染者和对照的MS及其组分基本概况

Table 2. Characteristics of MS and its components among HIV-infected patients and controls

代谢组分 文献 HIV感染者指标(vs.对照人群) P值 MS 22 比例↑ 0.004 23 比例↑ 0.220 HDL 5 均值↓ > 0.050 7 均值↓ < 0.001 14 均值↓ < 0.001 16 均值↓ 0.600 22 降低比例↑ 0.040 TG 5 均值↑ < 0.050 14 均值↑ < 0.001 16 均值↑ 0.290 22 升高比例↑ < 0.001 血脂异常(HDL↓或TG↑) 23 比例↑ < 0.001 HTN 5 比例↓ > 0.050 4 比例↑ 0.199 10 比例↑ 0.002 18 比例↓ 0.040 22 血压升高比例↑ 0.110 23 比例↑ 0.350 24 比例↑ 0.054 WC 10 均值↓ 0.010 22 升高比例↓ 0.130 23 比例↑ < 0.001 24 均值↓ BMI 5 均值↓ < 0.050 10 均值↓ < 0.001 16 均值↓ 0.003 18 过瘦及正常体重比例↑ < 0.001 22 均值相等 0.990 24 均值↓ DM (GHb) 5 均值↓,DM比例↓ < 0.050, > 0.050 7 现患比例↓ 0.558 10 比例↑ 0.736 11 比例、GHb中位值↑ 0.015, < 0.001 22 比例↑ 0.020 23 比例↑ 0.020 其它代谢组分 LDL 5 均值↓ < 0.050 7 均值↑ 0.861 14 均值↑ 0.080 16 均值↓ 0.260 TC 5 均值↑ 0.080 10 均值↑ 0.872 14 均值↑ 0.110 16 升高比例↑ 0.370 18 均值↑ < 0.001 WHR 10 均值↑ < 0.001 16 均值↑,升高比例↑ 0.020, 0.020 HOMA-IR 13 高分位数比例↑ 0.003 注:HDL:高密度脂蛋白(high density lipoprotein, LDL);TG:甘油三酯(triglyceride, TG);HTN:高血压(hypertension, HTN);WC:腰围(waist circumference, WC);BMI:体重指数(body mass index, BMI);DM:糖尿病(diabetes mellitus, DM);GHb:糖化血红蛋白(glycated hemoglobin, GHb);LDL:低密度脂蛋白(low density lipoprotein, LDL);TC:总胆固醇(total cholesterol, TC);WHR:腰臀比(waist-to-hip ratio, WHR);HOMA-IR:胰岛素抵抗指数(homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, HOMA-IR)。 表 3 HIV感染者MS或组分与神经认知功能损伤关联

Table 3. The association of MS and its components with neurocognitive impairment among HIV-infected patients

代谢组分 具体结局指标 效应方向及显著性 MS 运动速度,延迟的言语和非言语记忆[5];多领域神经认知功能紊乱[23]; 无关联 神经认知得分(GDS)[22] β (sx)=0.22 (0.10), P=0.030 糖代谢指标 DM 运动速度、延迟言语和非言语记忆[5];神经认知得分(QNPZ-5),NCI (QNPZ-5)[6];斯特鲁普干扰测试时长、符号数字测试[7];神经认知损伤[16];多领域神经认知功能紊乱[23] 无关联 HAD[3] OR (95% CI)=5.43 (1.66~17.70), P < 0.010 神经认知得分(GCI)9] β (95% CI)= 1.38 (0.38~2.38), P=0.007 神经认知得分(MNC法)[16] β (95% CI)= -0.73 (-1.40~-0.05), P=0.036 不同功能得分[18] 各个效应方向及性均不一致 HOMA-IR HAD [3] 无关联 神经认知损伤程度分类(正常,MCMD,HAD)[4] OR (95%CI) =1.12 (1.003~1.242), P=0.044 注意力、记忆力、语音流畅度[13] β注=-0.10, P < 0.010; β记=-0.10, P < 0.010; β语= -0.09, P= 0.020 胰岛素水平 神经认知下降(GDS)[21] OR (95% CI) =1.43 (1.13~1.80), P=0.003 空腹血糖 HAD[3];神经认知损伤程度分类(正常, ANI, MND, HAD)[12, 19] 无关联 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5] OR (95% CI) =0.59 (0.36~0.97), P=0.037 GHb 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5] 无关联 HTN 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5];斯特鲁普干扰测试时长、符号数字测试[7] 无关联 多领域神经认知功能紊乱[23] OR=3.79, P=0.019 肥胖指标 BMI 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5] 无关联 NCI (GDS) [8] OR=0.69 (0.49~0.98), P=0.038(纳入腰围) 不同测试得分[10] 各个效应方向及性均不一致 信息处理速度[17] β (sx) 肥胖=0.23 (2.15), P=0.033 NCI (GDS) [20] OR (95%CI) 过瘦=1.39 (1.03~1.87), P=0.029;OR (95%CI) 超重肥胖=1.38 (1.10~1.72), P=0.005 不同功能得分[24] 基线β (sx) 肥胖=-3.8 (1.8), P < 0.050;随访β (sx) 肥胖=3.2 (1.7), P < 0.050; WC/ WHR 神经认知得分(GDS) [22] 无关联 NCI (GDS) [8] OR (95% CI) =1.34 (1.13~1.60), P=0.001 NCI (GDS) [11] OR=2.89, P=0.004 多领域神经认知功能紊乱[23] OR=2.80, P=0.035 不同功能得分[24] 基线β (sx) 肥胖=-3.8(1.8), P < 0.050; 脂代谢指标 脂代谢异常 多领域神经认知功能紊乱[23] 正相关, P < 0.050 HDL 斯特鲁普干扰测试时长、符号数字测试(SDMT) [7];神经认知损伤程度分类(正常, ANI, MND, HAD) [19] 无关联 神经认知(得分)下降速度[14] 负相关, P=0.020 认知水平下降(分类指标) [21] 负相关, P < 0.010 TG 神经认知损伤程度分类(正常, ANI,MND, HAD) [19] 无关联 神经认知(得分)下降速度[14] 正相关, P=0.040 LDL 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5];神经认知得分(QNPZ-5),NCI (QNPZ-5) [6];斯特鲁普干扰测试时长、符号数字测试[7];神经认知损伤程度分类(正常, ANI, MND, HAD) [19] 无关联 神经认知(得分)下降速[14] 正相关, P=0.002 TC 运动速度,延迟言语和非言语记忆[5];神经认知损伤程度分类(正常, ANI, MND, HAD) [19] 无关联 神经认知得分(QNPZ-5) [6] 负相关, P=0.020 神经认知(得分)下降速度[14] 正相关, P=0.003 HAND进展[15] OR (95%CI) =2.80 (1.30~5.90), P=0.010 注:HDL:高密度脂蛋白(high density lipoprotein, LDL);TG:甘油三酯(triglyceride, TG);HTN:高血压(hypertension, HTN);WC:腰围(waist circumference, WC);BMI:身体体质指数(body mass index, BMI);DM:糖尿病(diabetes mellitus, DM);GHb:糖化血红蛋白(glycated hemoglobin, GHb);LDL:低密度脂蛋白(low density lipoprotein, LDL);TC:总胆固醇总胆固醇(total cholesterol, TC);WHR:腰臀比(waist-to-hip r atio, WHR);HOMA-IR:胰岛素抵抗指数(homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, HOMA-IR)。HAD:HIV相关痴呆(HIV-associated dementia, HAD);MCMD:轻微认知运动障碍(minor cognitive motor disorder, MCMD);NCI:神经认知损伤(neurocognitive impairment, NCI);ANI:无症状神经认知损伤(asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment, ANI);MND:轻微神经认知障碍(mild neurocognitive disorder, MND);QNPZ-5:神经认知表现量化z得分(quantitative NP z-score of the 5 tests, QNPZ-5);MNC:多元规范比较(multivariate normative comparison, MNC);GDS,总体神经认知损伤得分(global deficit score, GDS);GCI,全球认知障碍(global cognitive impairment, GCI)。 -

[1] Carr A, Samaras K, Burton S, et al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitors[J]. AIDS, 1998, 12(7):F51-F58. DOI: 10.1097/00002030-199807000-00003. [2] Fernandes NC, Pulliam L. Inflammatory mechanisms and cascades contributing to neurocognitive impairment in HIV/AIDS[J]. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 2019:1-27. DOI: 10.1007/7854-2019-100. [3] Valcour V, Shikuma CM, Shiramizu B, et al. Diabetes, insulin resistance, and dementia among HIV-1-infected patients[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2005, 38(1):31-36. DOI: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00006. [4] Valcour V, Sacktor N, Paul RH, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with cognition among HIV-1-infected patients: the Hawaii aging with HIV cohort[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2006, 43(4):405-410. DOI: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243119.67529.f5. [5] Becker JT, Kingsley LA, Mullen J, et al. Vascular risk factors, HIV serostatus, and cognitive dysfunction in gay and bisexual men[J]. Neurology, 2009, 73(16):1292-1299. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd10e7. [6] Wright EJ, Grund B, Robertson KR, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with lower baseline cognitive performance in HIV-positive persons[J]. Neurology, 2010, 75(10):864-873. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11bd8. [7] Crystal H, Weedon J, Holman S, et al. Associations of cardiovascular variables and HAART with cognition in middle-aged HIV-infected and uninfected women[J]. J Neurovirol, 2011, 17(5): 469-476. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-011-0052-3. [8] Mccutchan JA, Marquiebeck J, Fitzsimons C, et al. Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder[J]. Neurology, 2012, 78(7):485-492. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182478d64. [9] Fabbiani M, Ciccarelli N, Tana M, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness are associated with lower cognitive performance in HIV-infected patients[J]. HIV Med, 2013, 14(3):136-144. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01044.x. [10] Gustafson D, Mielke MM, Tien PC, et al. Anthropometric measures and cognition in middle-aged HIV-infected and uninfected women. The Women's Interagency HIV Study[J]. J Neurovirol, 2013, 19(6):574-585. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-013-0219-1. [11] Sattler FR, He J, Letendre S, et al. Abdominal obesity contributes to neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected patients with increased inflammation and immune activation[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2015, 68(3):281-288. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000458. [12] Dufouil C, Richert L, Thiébaut R, et al. Diabetes and cognitive decline in a French cohort of patients infected with HIV-1[J]. Neurology, 2015, 85(12):1065-1073. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001815. [13] Valcour V, Rubin LH, Tien P, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) modulates the associations between insulin resistance and cognition in the current combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) era: a study of the Women's Interagency HIV Study (WIHS)[J]. J Neurovirol, 2015, 21(4):415-421. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-015-0330-6. [14] Mukerji SS, Locascio JJ, Misra V, et al. Lipid profiles and APOE4 allele impact midlife cognitive decline in HIV-infected men on antiretroviral therapy[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2016, 63(8):1130-1139. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciw495. [15] Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Seaberg E, et al. Prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study[J]. Neurology, 2016, 86(4):334-340. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002277. [16] Schouten J, Su T, Wit FW, et al. Determinants of reduced cognitive performance in HIV-1-infected middle-aged men on combination antiretroviral therapy[J]. AIDS, 2016, 30(7):1027-38. DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001017. [17] Okafor CN, Kelso NE, Bryant V, et al. Body mass index, inflammatory biomarkers and neurocognitive impairment in HIV-infected persons[J]. Psychol Health Med, 2017, 22(3):289-302. DOI: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1199887. [18] Yang J, Jacobson LP, Becker JT, et al. Impact of glycemic status on longitudinal cognitive performance in men with and without HIV infection[J]. AIDS, 2018, 32(13):1849-1860. DOI: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001842. [19] Gascón MRP, Vidal JE, Mazzaro YM, et al. Neuropsychological assessment of 412 HIV-infected individuals in Sao Paulo, Brazil[J]. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2018, 32(1):1-8. DOI: 10.1089/apc.2017.0202. [20] Jumare J, El-Kamary SS, Magder L, et al. Brief report: body mass index and cognitive function among HIV-1-infected individuals in China, India, and Nigeria[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2019, 80(2):e30-e35. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001906. [21] Khuder SS, Chen S, Letendre S, et al. Impaired insulin sensitivity is associated with worsening cognition in HIV-infected patients[J]. Neurology, 2019, 92(12):e1344-e1353. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007125. [22] Yu B, Pasipanodya E, Montoya JL, et al. Metabolic syndrome and neurocognitive deficits in HIV infection[J]. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2019, 81(1):95-101. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001964. [23] Pasipanodya EC, Montoya JL, Campbell LM, et al. Metabolic risk factors as differential predictors of profiles of neurocognitive impairment among older HIV+ and HIV- adults: an observational study[J]. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 2019:acz040. DOI: 10.1093/arclin/acz040. [24] Rubin LH, Gustafson D, Hawkins KL, et al. Midlife adiposity predicts cognitive decline in the prospective Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study[J]. Neurology, 2009, 93(3):e261-e271. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007779. [25] Dore GJ, Correll PK, Li Y, et al. Changes to AIDS dementia complex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy[J]. AIDS, 1999, 13(10):1249-1253. DOI: 10.1097/00002030-199907090-00015. [26] Grant I, Franklin DR Jr, Deutsch R, et al. Asymptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment increases risk for symptomatic decline[J]. Neurology, 2014, 82(23):2055-2062. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000492. [27] Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Seripa D, et al. Metabolic-cognitive syndrome: a cross-talk between metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2010, 9(4):399-417. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.04.007. [28] Crichton GE, Elias MF, Buckley JD, et al. Metabolic syndrome, cognitive performance, and dementia[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2012, 30(Suppl 2):S77-S87. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111022. [29] Craft S. The role of metabolic disorders in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: two roads converged[J]. Arch Neurol, 2009, 66(3):300-305. DOI: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.27. [30] 杨馨, 杨峥嵘. HIV相关神经认知功能障碍的研究进展[J].国际流行病学传染病学杂志, 2016, 43(5):333-337. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4149.2016.05.011.Yang X, Yang ZR. Research progress on HIV-related neurocognitive dysfunction[J]. Inter J Epidemiol Infect Dis, 2016, 43(5):333-337. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-4149.2016.05.011. [31] Ene L, Duiculescu D, Ruta SM. How much do antiretroviral drugs penetrate into the central nervous system?[J]. J Med Life, 2011, 4(4):432-439. http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC3227164/ [32] Soulie C, Grudé M, Descamps D, et al. Antiretroviral-treated HIV-1 patients can harbour resistant viruses in CSF despite an undetectable viral load in plasma[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2017, 72(8):2351-2354. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkx128. [33] Hong S, Banks WA. Role of the immune system in HIV-associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2015, 45:1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.10.008. [34] De Benedetto I, Trunfio M, Guastamacchia G, et al. A review of the potential mechanisms of neuronal toxicity associated with antiretroviral drugs[J]. J Neurovirol, 2020, 26(5):642-651. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-020-00874-9. [35] Gonzalez H, Podany A, Al-Harthi L, et al. The far-reaching HAND of cART: cART effects on astrocytes[J]. J Neuroimmune Pharm, 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s11481-020-09907-w. [36] 田金洲, 解恒革, 秦斌, 等.中国简短认知测试在痴呆诊断中的应用指南[J].中华医学杂志, 2016, 96(37):2945-2959. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.37.001.Tian JZ, Xie HG, Qin B, et al. Guidelines for the application of the Chinese brief cognitive test in the diagnosis of dementia[J]. Natl Med J Chin, 2016, 96(37):2945-2959. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.37.001. [37] Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort[J]. Neurology, 2004, 63(5):822-827. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134665.58343.8d. -

下载:

下载: