-

摘要:

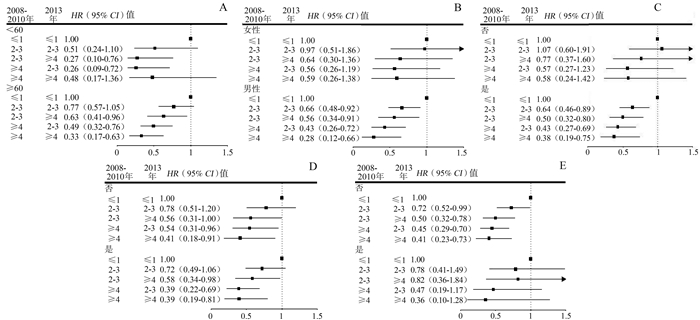

目的 探讨中老年人群生活方式及变化与新发脑卒中的关联。 方法 选取东风同济队列基线(2008-2010年)无心血管病、癌症及生活方式无缺失,且随访至2018年12月的18 293名研究对象。健康生活方式评分包括不吸烟、适度锻炼、均衡膳食、正常体重和适宜睡眠时长5项因素之和。采用Cox回归评估生活方式及变化与脑卒中的风险比(hazard ratio, HR)和95% CI值。 结果 平均9.5年随访后,新发脑卒中病例共1 549(8.5%)。校正混杂变量后,与基线生活方式评分≤1相比,2、3和≥4分组的新发脑卒中的HR(95% CI)分别为0.83(0.72~0.95)、0.72(0.63~0.83)和0.54(0.45~0.66)。5年间生活方式评分变化(基线至2013随访)结果显示,5年间生活方式评分一直维持在≥4分是维持≤1分新发脑卒中的0.39倍(HR=0.39, 95% CI: 0.23~0.67);当从基线2~3分提高至随访≥4分是维持≤1分新发脑卒中的0.55倍(HR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.37~0.81),但是从基线≤1分提高至随访≥4分并无保护作用(HR=1.17, 95% CI: 0.58~2.36)。 结论 在中老年人群中,尽早改善并长期保持健康生活方式对于脑卒中防控效益最大。 Abstract:Objective To explore the association of lifestyle and its changes with incident stroke in the middle-aged and older population. Methods A total of 18 293 participants who were free of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, or missing data on lifestyle at baseline were selected and followed until December 2018 from Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. The healthy lifestyle score included the sum of five factors: non-smoking, moderate physical activity, balanced diet, normal weight, and appropriate sleep duration. Cox regression was adopted to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of lifestyle and its changes with stroke. Results During the 9.5- years of follow-up, 1 549 (8.5%) stroke events were documented. Comparing with ≤1 score group at baseline, the HR (95% CI) of stroke was 0.83 (0.72-0.95), 0.72 (0.63-0.83), and 0.54 (0.45-0.66) for those with scores of 2, 3, and ≥4, respectively, after adjustment of confounders. The results of five- year lifestyle change (baseline to 2013 follow-up) showed that maintenance of ≥4 scores in healthy lifestyle had 0.39- fold (HR=0.39, 95% CI: 0.23-0.67) risk for incident stroke, compared to maintenance of ≤1 score group. Increment in healthy lifestyle score from 2-3 to ≥4 had 0.55- fold (HR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.37-0.81) risk of incident stroke; improvement from ≤1 to ≥4 scores showed no protective effects for stroke (HR=1.17, 95% CI: 0.58-2.36). Conclusions Among middle-aged and older Chinese adults, early improvement and long-term maintenance of a healthy lifestyle are most beneficial for preventing and controlling stroke. -

表 1 基线研究对象根据有无脑卒中的人口学特征分布情况[n (%)]

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants according to stroke at baseline[n (%)]

变量 总脑卒中(n=1 549) IS(n=1 246) HS(n=303) 无脑卒中(n=16 744) t/χ2值a P值a F/χ2值b P值a 年龄[ (x±s), 岁] 66.47±7.41 66.60±7.45 65.90±7.23 62.40±7.62 -20.13 < 0.001 203.71 < 0.001 女性 619(39.96) 493(39.57) 126(41.58) 9 669(57.75) 182.22 < 0.001 182.63 < 0.001 受教育程度 62.53 < 0.001 66.78 < 0.001 小学及以下 575(37.48) 452(36.69) 123(40.73) 4 657(28.01) 初中或高中 835(54.43) 686(55.68) 149(49.34) 10 262(61.73) 大学及以上 124(8.08) 94(7.63) 30(9.93) 1 705(10.26) 已婚/再婚 1 375(88.88) 1 101(88.50) 274(90.43) 15 098(90.39) 3.67 0.055 4.70 0.096 健康生活方式及评分(分) 当前不吸烟 1 143(73.79) 915(73.43) 228(75.25) 13 753(82.14) 65.33 < 0.001 65.86 < 0.001 适度锻炼(7~ < 10 h/周) 388(25.05) 310(24.88) 78(25.74) 4 289(25.62) 0.24 0.625 0.34 0.846 均衡膳食c 598(38.61) 473(37.96) 125(41.25) 7 622(45.52) 27.40 < 0.001 28.47 < 0.001 正常体重(18.5~ < 24 kg/m2) 594(38.35) 465(37.32) 129(42.57) 7 611(45.46) 28.96 < 0.001 31.68 < 0.001 适宜睡眠时长(7~8 h/d) 796(51.39) 635(50.96) 161(53.14) 9 271(55.37) 9.08 0.003 9.55 0.009 ≤1 369(23.82) 305(24.48) 64(21.12) 2 764(16.51) 90.97 < 0.001 95.53 < 0.001 2 540(34.86) 442(35.47) 98(32.34) 5 332(31.84) 3 462(29.83) 359(28.81) 103(33.99) 5 577(33.31) ≥4 178(11.49) 140(11.24) 38(12.54) 3 071(18.34) 脑卒中家族史 51(3.38) 41(3.38) 10(3.38) 761(4.65) 5.14 0.023 5.14 0.077 高血压 1 083(69.92) 859(68.94) 224(73.93) 8 091(48.32) 264.47 < 0.001 266.89 < 0.001 高脂血症 878(56.68) 722(57.95) 156(51.49) 8 338(49.80) 26.88 < 0.001 30.95 < 0.001 T2DM 381(24.60) 321(25.76) 60(19.80) 2 558(15.28) 91.32 < 0.001 97.74 < 0.001 注:IS表示缺血型脑卒中;HS表示出血型脑卒中;T2DM表示2型糖尿病;连续性变量以x±s表示;分类变量以n(%)表示;a表示比较总脑卒中与无脑卒中两组间差异;b表示较IS、HS与无脑卒中三组间差异;c表示均衡膳食至少有以下4项:每天吃蔬菜、每天吃水果、每周吃红肉1~6 d、每周吃豆类≥4 d、每周吃鱼≥1 d和经常饮茶。 表 2 生活方式评分与脑卒中及其亚型的风险比和CI

Table 2. HR and 95% CI for incident stroke and subtypes by lifestyle score

变量 健康生活方式评分(分) 每增加1分 P值 ≤1 2 3 ≥4 脑卒中 病例数/人年 369/28 710 540/55 445 462/57 881 178/31 552 模型1 1 0.76(0.66~0.87) 0.62(0.54~0.71) 0.43(0.36~0.52) 0.79(0.75~0.82) < 0.001 模型2 1 0.83(0.72~0.95) 0.72(0.63~0.83) 0.54(0.45~0.66) 0.84(0.80~0.88) < 0.001 IS 病例数/人年 305/30 690 442/58 247 359/60 315 140/32 739 模型1 1 0.77(0.66~0.89) 0.60(0.52~0.70) 0.43(0.35~0.52) 0.78(0.74~0.82) < 0.001 模型2 1 0.84(0.72~0.98) 0.70(0.59~0.82) 0.52(0.43~0.65) 0.83(0.78~0.87) < 0.001 HS 病例数/人年 64/31 867 98/59 860 103/61 594 38/33 178 模型1 1 0.81(0.59~1.12) 0.83(0.61~1.14) 0.57(0.38~0.85) 0.88(0.79~0.98) 0.022 模型2 1 0.85(0.62~1.18) 0.95(0.69~1.31) 0.72(0.48~1.08) 0.95(0.85~1.06) 0.336 注:IS表示缺血型脑卒中;HS表示出血型脑卒中;模型1未调整因素;模型2调整年龄、性别、受教育程度、婚姻状况、脑卒中家族史。 表 3 5年间生活方式评分变化与脑卒中及其亚型的关联

Table 3. The association of lifestyle change during five-year period with stroke and its subtype

5年间生活方式评分变化 脑卒中 IS HS 2008-2010年 2013年 病例数/人年 HR (95% CI)值a 病例数/人年 HR (95% CI)值a 病例数/人年 HR (95% CI)值a ≤1 ≤1 62/4 037 1.00 54/4 189 1.00 8/4 329 1.00 ≤1 2~3 89/7 101 0.92(0.66~1.28) 71/7 379 0.86(0.59~1.24) 18/7 537 1.32(0.57~3.06) ≤1 ≥4 10/624 1.17(0.58~2.36) 7/659 0.87(0.37~2.04) 3/661 2.81(0.75~10.61) 2~3 ≤1 84/6 489 0.95(0.68~1.33) 67/6 735 0.88(0.60~1.27) 17/6 901 1.37(0.59~3.21) 2~3 2~3 312/33 780 0.73(0.55~0.98) 247/34 784 0.67(0.49~0.92) 65/35 277 1.17(0.56~2.45) 2~3 ≥4 51/7 912 0.55(0.37~0.81) 43/8 037 0.55(0.36~0.84) 8/8 148 0.62(0.22~1.74) ≥4 ≤1 10/676 1.12(0.57~2.21) 8/714 0.98(0.46~2.09) 2/724 1.76(0.37~8.31) ≥4 2~3 48/8 762 0.45(0.30~0.67) 37/9 005 0.40(0.25~0.62) 11/9 059 0.80(0.31~2.05) ≥4 ≥4 18/4 419 0.39(0.23~0.67) 16/4 480 0.41(0.23~0.73) 2/4 512 0.34(0.07~1.64) 注:IS表示缺血型脑卒中;HS表示出血型脑卒中;a模型调整年龄、性别、受教育程度、婚姻状况、脑卒中家族史。 -

[1] 王陇德, 刘建民, 杨弋, 等. 我国脑卒中防治仍面临巨大挑战——《中国脑卒中防治报告2018》概要[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2019, 34(2): 105-119. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.02.001.Wang LD, Liu JM, Yang Y, et al. The prevention and treatment of stroke still face huge challenges----brief report on stroke prevention and treatment in China, 2018[J]. Chin Circul J, 2019, 34(2): 105-119. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.02.001. [2] 《中国脑卒中防治报告2019》编写组. 《中国脑卒中防治报告2019》概要[J]. 中国脑血管病杂志, 2020, 17(5): 272-281. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5921.2020.05.008.Report on stroke prevention and treatment in China Writing Group. Brief report on stroke prevention and treatment in China, 2019[J]. Chin J Cerebrovasc Dis, 2020, 17(5): 272-281. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-5921.2020.05.008. [3] Fang EF, Xie C, Schenkel JA, et al. A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century (2nd edition): focusing on basic and translational research, long-term care, policy and social networks[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2020, 64: 101174. DOI: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101174. [4] Zhou Y, Yan S, Song X, et al. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke in Hubei, China: a survey of thrombolysis rate and barriers[J]. BMC Neurol, 2019, 19(1): 202. DOI: 10.1186/s12883-019-1418-z. [5] Liu G, Li Y, Hu Y, et al. Influence of lifestyle on incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018, 71(25): 2867-2876. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.027. [6] Jain P, Suemoto CK, Rexrode K, et al. Hypothetical lifestyle strategies in middle-aged women and the long-term risk of stroke[J]. Stroke, 2020, 51(5): 1381-1387. DOI: 10.1161/strokeaha.119.026761. [7] Larsson SC, Akesson A, Wolk A. Healthy diet and lifestyle and risk of stroke in a prospective cohort of women[J]. Neurology, 2014, 83(19): 1699-1704. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000954. [8] Tikk K, Sookthai D, Monni S, et al. Primary preventive potential for stroke by avoidance of major lifestyle risk factors: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition-Heidelberg cohort[J]. Stroke, 2014, 45(7): 2041-2046. DOI: 10.1161/strokeaha.114.005025. [9] Wang C, Bangdiwala SI, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of estimated sleep duration and naps with mortality and cardiovascular events: a study of 116 632 people from 21 countries[J]. Eur Heart J, 2019, 40(20): 1620-1629. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy695. [10] Zhou L, Yu K, Yang L, et al. Sleep duration, midday napping, and sleep quality and incident stroke[J]. Neurology, 2020, 94(4): e345-e356. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000008739. [11] Lv J, Yu C, Guo Y, et al. Adherence to healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases in the Chinese population[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017, 69(9): 1116-1125. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.076. [12] Wang F, Zhu J, Yao P, et al. Cohort Profile: the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study of retired workers[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2013, 42(3): 731-740. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dys053. [13] 何美安, 张策, 朱江, 等. 东风-同济队列研究: 研究方法及调查对象基线和第一次随访特征[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2016, 37(4): 480-485. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.04.008.He MA, Zhang C, Zhu J, et al. Dongfeng-Tongji cohort: methodology of the survey and the characteristics of baseline and initial population of follow-up program[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2016, 37(4): 480-485. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.04.008. [14] Inoue-Choi M, Liao LM, Reyes-Guzman C, et al. Association of long-term, low-Intensity smoking with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study[J]. JAMA Intern Med, 2017, 177(1): 87-95. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7511. [15] Zhu N, Yu C, Guo Y, et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Chinese adults: a 10-year prospective study of 0.5 million people[J]. Int J Behav Nutr Phy, 2019, 16(1): 98. DOI: 10.1186/s12966-019-0860-z. [16] Chen C, Lu FC. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults[J]. Biomed Environ Sci, 2004, 17Suppl: 1-36. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00991.x. [17] Hu C, Zhang Y, Yu Y, et al. Association of drinking pattern with risk of coronary heart disease incidence in the middle-aged and older Chinese men: results from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(5): e0178070. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178070. [18] Larsson SC, Åkesson A, Wolk A. Primary prevention of stroke by a healthy lifestyle in a high-risk group[J]. Neurology, 2015, 84(22): 2224-2228. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001637. [19] Zhang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, et al. Lifestyle factors on the risks of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2011, 171(20): 1811-1818. DOI: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.443. [20] Chiuve SE, Rexrode KM, Spiegelman D, et al. Primary prevention of stroke by healthy lifestyle[J]. Circulation, 2008, 118(9): 947-954. DOI: 10.1161/circulationaha.108.781062. [21] Yang LL, Yang HD, He MA, et al. Longer sleep duration and midday napping are associated with a higher risk of CHD incidence in middle-aged and older Chinese: the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort study[J]. Sleep, 2016, 39(3): 645-652. DOI: PⅡsp-00311-1510.5665/sleep.5544. [22] Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Spijkerman AM, Kromhout D, et al. Sufficient sleep duration contributes to lower cardiovascular disease risk in addition to four traditional lifestyle factors: the morgen study[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2014, 21(11): 1367-1375. DOI: 10.1177/2047487313493057. [23] Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Gross MD, et al. Combined lifestyle factors and cardiovascular disease mortality in Chinese men and women: the Singapore Chinese health study[J]. Circulation, 2011, 124(25): 2847-2854. DOI: 10.1161/circulationaha.111.048843. [24] Hulsegge G, Looman M, Smit HA, et al. Lifestyle changes in young adulthood and middle age and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: the Doetinchem cohort study[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2016, 5(1): e002432. DOI: 10.1161/jaha.115.002432. [25] Perak AM, Ning H, Khan SS, et al. Associations of late adolescent or young adult cardiovascular health with premature cardiovascular disease and mortality[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2020, 76(23): 2695-2707. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.002. [26] Qi W, Ma J, Guan T, et al. Risk factors for incident stroke and its subtypes in China: a prospective study[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2020, 9(21): e016352. DOI: 10.1161/jaha.120.016352. [27] Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American heart association[J]. Circulation, 2019, 139(10): e56-e528. DOI: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000659. [28] Long GH, Cooper AJM, Wareham NJ, et al. Healthy behavior change and cardiovascular outcomes in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients: a cohort analysis of the Addition-Cambridge study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2014, 37(6): 1712-1720. DOI: 10.2337/dc13-1731. -

下载:

下载: