-

摘要:

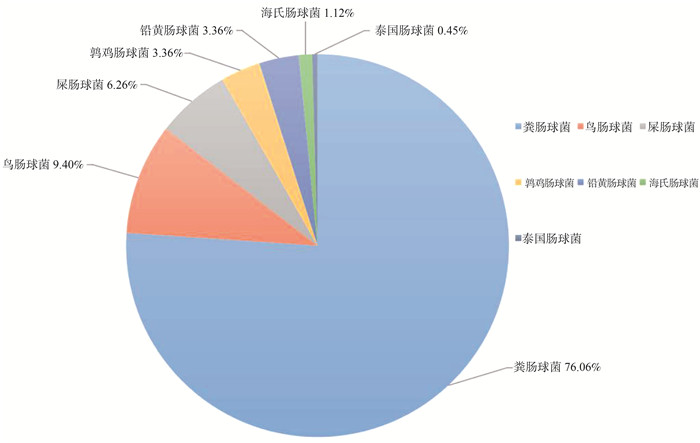

目的 研究深圳市健康人群肠道携带optrA阳性肠球菌流行率及其风险因素。 方法 共调取2018—2019年社区健康体检者粪便样本565份,采用肠球菌选择培养基筛选耐氟苯尼考肠球菌,使用MALDI-TOF MS(MALDI Biotyper, Bruker, Germany)进行种属鉴定及PCR鉴定optrA基因。以optrA阳性肠球菌的携带者作为病例,以年龄为匹配条件,按1∶4匹配未携带者作为对照。采用多因素logistic回归分析模型分析optrA阳性肠球菌定植于健康人群肠道的风险因素。 结果 2018—2019年深圳市健康人群肠道中optrA基因的流行率为18.10%(102/565,95% CI: 14.90%~21.20%),从基因阳性人群粪便中共分离447株optrA阳性肠球菌,粪肠球菌为最主要流行种属(76.06%)。猪肉日摄入量>50.0 g (OR=1.615,95% CI: 1.017~2.565,P=0.042)、3个月内住院治疗(OR=11.551,95% CI: 2.153~61.963,P=0.004)是optrA阳性肠球菌在健康人群肠道中定植的危险因素。 结论 optrA阳性肠球菌在深圳市健康人群肠道中已广泛流行,其可能通过食物链传播至人类,同时住院治疗将增加optrA阳性肠球菌在健康人群肠道中定植的风险。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of optrA-positive Enterococcus in the healthy people in Shenzhen City. Methods A total of 565 feces of the healthy pepople during 2018-2019 was cultured on enterococcal-selective plates to obtain florfenicol-resistant Enterococcus. MALDI Biotyper, Bruker, Germany (MALDI-TOF MS) was used for the species identification and PCR was used for optrA gene confirmation. People carrying optrA-positive enterococci were defined as positive cases and four times people with optrA-negative were randomly selected as control cases using the age of matching condition. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to analyze the risk factors of optrA-positive Enterococcus colonization in the human intestines. Results Overall, the prevalence of optrA-positive individuals was 18.10% (102/565, 95% CI: 14.90%-21.20%) in Shenzhen during 2018-2019. A total of 447 optrA-enterococci strains was isolated from the above samples, of which the Enterococcus faecalis was the most prevalent species (76.06%). Pork intake >50 g/d (OR=1.615, 95% CI: 1.017-2.565, P=0.042) and hospitalization within 3 months (OR=11.551, 95% CI: 2.153-61.963, P=0.004) were risk factors for optrA-positive Enterococcus colonization in the healthy human intestines. Conclusions optrA-positive Enterococcus have been already widespread in the human intestines in Shenzhen, and these bacteria may spread to humans through the food chain. Meanwhile, hospitalization will increase the risk of optrA-positive Enterococcus colonizing in the healthy hunman intestines. -

Key words:

- Linezolid /

- Enterococcus /

- optrA /

- Prevalence /

- Risk factors

-

表 1 研究人群一般情况[n(%)]

Table 1. General situation of the study population [n(%)]

变量 optrA阳性肠球菌定植病例组 χ2/U值 P值 变量 optrA阳性肠球菌定植病例组 χ2/U值 P值 有(n=102) 无(n=408) 有(n=102) 无(n=408) 性别 0.009 0.926 饮料 3.345 0.067 男性 36(35.3) 146(35.8) 无或极少 89(87.3) 376(92.8) 女性 66(64.7) 262(64.2) 每周1次以上 13(12.7) 29(7.2) 年龄[M (P25,P75), 岁] 56(46, 64) 59(50, 64) -1.740 0.082 宠物 0.153 0.695 高血压 0.893 0.345 无 96(94.1) 386(95.1) 无 82(80.4) 310(76.0) 有 6(5.9) 20(4.9) 有 20(19.6) 98(24.0) 饮用水烧开 0.400 0.527 b 高血脂 0.084 0.772 无 4(3.9) 9(2.2) 无 85(83.3) 335(82.1) 有 98(96.1) 399(97.8) 有 17(16.7) 73(17.9) 饮食种类 0.32 0.866 a 糖尿病 0.129 0.661 非素食者 78(76.5) 316(77.5) 无 96(94.1) 379(92.9) 素食者 24(23.5) 90(22.5) 有 6(5.9) 29(7.1) 参加锻炼 0.455 0.5 胃肠道疾病 1.618 0.203 无 22(21.6) 76(18.6) 有 90(88.2) 339(83.1) 有 80(78.4) 332(81.4) 无 12(11.8) 69(16.9) 医疗接触史(3个月内) c 6.572 0.01 吸烟史 3.812 0.149 无 92(90.2) 393(96.3) 无 87(85.3) 325(79.7) 有 10(9.8) 15(3.7) 有 4(3.9) 41(10.0) 住院治疗(3个月内) c 8.700 0.003 b 已戒烟 11(10.8) 142(10.3) 无 97(95.1) 406(99.5) 饮酒史 0.872 0.647 b 有 5(4.9) 2(0.5) 无 82(80.4) 330(80.9) 抗生素(3个月) 1.106 0.293 有 17(16.7) 59(14.5) 无 94(92.2) 387(94.9) 已戒酒 3(2.9) 19(4.6) 有 8(7.8) 21(5.1) 注:a连续性校正;b Fisher确切概率法计算所得值;cP < 0.05。 表 2 研究人群的食物日摄入量的比较[n(%)]

Table 2. Comparison of the daily food intake of the study population [n(%)]

变量(g) M(P25, P75) optrA阳性肠球菌定植 χ2/U值 P值 变量(g) M (P25, P75) optrA阳性肠球菌定植 χ2/U值 P值 有(n=102) 无(n=408) 有(n=102) 无(n=408) 大米 250.0(121.3, 500.0) 0.200 0.655 鸭肉 7.1(0.0, 21.4) 0.002 0.965 ≤250.0 60(58.8) 230(56.4) ≤7.1 49(48.0) 195(47.8) >250.0 42(41.2) 178(43.6) >7.1 53(52.0) 213(52.2) 面粉 50.0(11.5, 100.0) 0.128 0.720 淡水鱼a 21.4(7.1, 42.7) 4.521 0.033 ≤50.0 60(58.8) 232(56.9) ≤21.4 62(60.8) 200(49.0) >50.0 42(41.2) 176(43.1) >21.4 40(39.2) 208(51.0) 杂粮 6.9(1.1, 14.2) 0.110 0.740 海鲜 4.9(0.1, 14.3) 1.666 0.640 ≤6.9 14(13.7) 51(12.5) ≤4.9 55(53.9) 196(48.0) >6.9 88(86.3) 357(87.5) >4.9 47(46.1) 212(52.0) 猪肉 50.0(21.4, 100.0) 2.846 0.092 奶制品 71.2(3.6, 249.8) 0.099 0.752 ≤50.0 47(46.1) 226(55.4) ≤71.2 43(42.2) 165(40.4) >50.0 55(53.9) 182(44.6) >71.2 59(57.8) 243(59.6) 牛肉 6.9(1.1, 14.3) 0.196 0.658 鸡蛋 50.0(21.4, 50.0) 0.099 0.752 ≤6.9 53(52.0) 202(49.5) ≤50.0 92(90.2) 382(93.6) >6.9 49(48.0) 206(50.5) >50.0 10(9.8) 26(6.4) 羊肉 0.4(0.0, 3.3) 0.237 0.626 蔬菜 150.0(200.0, 300.0) ≤0.4 49(48.0) 207(50.7) ≤200.0 57(55.9) 217(53.2) >0.4 53(52.0) 201(49.3) >200.0 45(44.1) 191(46.8) 鸡肉 8.2(3.3, 28.5) 0.002 0.965 油类 30.0(48.2, 68.9) 1.225 0.268 ≤8.2 51(50.0) 205(50.2) ≤48.2 56(54.9) 199(48.8) >8.2 51(50.0) 203(49.8) >48.2 46(45.1) 209(51.2) 注:aP < 0.05。 表 3 多因素logistic回归分析

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

风险因素 分类 模型1 模型2 OR (95% CI)值 P值 OR (95% CI)值 P值 淡水鱼日摄入量(g) >21.4 0.571(0.359~0.907) 0.018 0.527(0.327~0.850) 0.009 猪肉日摄入量(g) >50.0 1.744(1.107~2.749) 0.016 1.615(1.017~2.565) 0.042 住院治疗(3个月内) 有 11.357(2.139~60.303) 0.004 11.551(2.153~61.963) 0.004 饮料摄入 每周1次以上 2.335(1.140~4.784) 0.020 2.335(0.954~4.784) 0.066 注:模型1:纳入淡水鱼、猪肉摄入量、住院治疗及饮料摄入;模型2:纳入淡水鱼、猪肉摄入量、住院治疗及饮料摄入,并调整性别、年龄。 -

[1] Pfaller MA, Mendes RE, Streit JM, et al. Five year summary of in vitro activity and resistance mechanisms of linezolid against clinically important gram-positive cocci in the United States from the LEADER surveillance program (2011 to 2015)[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017, 61(7): e00609-17. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00609-17. [2] Cho SY, Kim HM, Chung DR, et al. Resistance mechanisms and clinical characteristics of linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates: a single-centre study in South Korea[J]. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2018, 12: 44-47. DOI: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.09.009. [3] Li BB, Wu CM, Wang Y, et al. Single and dual mutations at positions 2 058, 2 503 and 2 504 of 23S rRNA and their relationship to resistance to antibiotics that target the large ribosomal subunit[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2011, 66(9): 1983-1986. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkr268. [4] Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw J. Novel ribosomal mutations in Staphylococcus aureus strains identified through selection with the oxazolidinones linezolid and torezolid (TR-700)[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009, 53(12): 5265-5274. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00871-09. [5] Locke JB, Hilgers M, Shaw KJ. Mutations in ribosomal protein L3 are associated with oxazolidinone resistance in staphylococci of clinical origin[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2009, 53(12): 5275-5278. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01032-09. [6] Li DX, Cheng YM, Schwarz S, et al. Identification of a poxtA- and cfr-carrying multiresistant Enterococcus hirae strain[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2020, 75(2): 482-484. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkz449. [7] Wang Y, Lyv Y, Cai J, et al. A novel gene optrA that confers transferable resistance to oxazolidinones and phenicols and its presence in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium of human and animal origin[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015, 70(8): 2182-2190. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv116. [8] Ero R, Kumar V, Su WX, et al. Ribosome protection by ABC-F proteins-Molecular mechanism and potential drug design[J]. Protein Sci, 2019, 28(4): 684-693. DOI: 10.1002/pro.3589. [9] Fan R, Li DX, Fessler AT, et al. Distribution of optrA and cfr in florfenicol-resistant staphylococcus sciuri of pig origin[J]. Vet Microbiol, 2017, 210: 43-48. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.07.030. [10] Cai J, Wang Y, Schwarz S, et al. Enterococcal isolates carrying the novel oxazolidinone resistance gene optrA from hospitals in Zhejiang, Guangdong, and Henan, China, 2010-2014[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2015, 21(12): 1091-1095. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.007. [11] Cai J, Schwarz S, Chi D, et al. Faecal carriage of optrA-positive enterococci in asymptomatic healthy humans in Hangzhou, China[J]. Clin Microbil Infect, 2019, 25(5): 630-631. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.07.025. [12] Wang YY, Li XW, Fu YL, et al. Association of florfenicol residues with the abundance of oxazolidinone resistance genes in livestock manures[J]. J Hazard Materi, 2020, 399: 123059. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123059. [13] Na SH, Moon DC, Choi MJ, et al. Detection of oxazolidinone and phenicol resistant enterococcal isolates from duck feces and carcasses[J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2019, 293: 53-59. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.01.002. [14] Lyu Z, Shen Y, Liu W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of mcr-1-positive volunteers after colistin banning as animal growth promoter in China: a community-based case-control study[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2021, 28(2): 267-272. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.033. [15] Kaluza J, Harris HR, Linden A, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective cohort study of men[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 2019, 188(5): 907-916. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwz020. [16] Hu S, Lyv Z, Xiang Q, et al. Dietary factors of blaNDM carriage in health community population: a cross-sectional study[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(11): 5959. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18115959. [17] Feng B, Shi HM, Xu FX, et al. FTIR-assisted MALDI-TOF MS for the identification and typing of bacteria[J]. Anal Chim Acta, 2020, 1111: 75-82. DOI: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.03.037. [18] 李德喜. 恶唑烷酮类耐药基因cfr和optrA在猪源MRSA和CoNS中流行及传播机制的研究[D]. 北京: 中国农业大学, 2016.Li DX. The epide miological study on the oxazolidinone resistance genes cfr and optrA and theirs transmission mechanism among MRSA and CoNS isolates from swine[D]. Beijin: China Agricultural University, 2016. [19] Pan M, Chu LM. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in soils from wastewater irrigation areas in the Pearl River Delta region, Southern China[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2018, 624: 145-152. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.008. [20] De Smet J, Boyen F, Croubels S, et al. Similar gastro-intestinal exposure to florfenicol after oral or intramuscular administration in pigs, leading to resistance selection in commensal escherichia coli[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2018, 9: 1265. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01265. [21] Zhao Q, Wang Y, Wang SL, et al. Prevalence and abundance of florfenicol and linezolid resistance genes in soils adjacent to swine feedlots[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6(1): 32192. DOI: 10.1038/srep32192. [22] Chen L, Han DR, Tang ZY, et al. Co-existence of the oxazolidinone resistance genes cfr and optrA on two transferable multi-resistance plasmids in one Enterococcus faecalis isolate from swine[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2020, 56(1): 105993. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105993. [23] Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network at the centers for disease control and prevention, 2011-2014[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2016, 37(11): 1288-1301. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. [24] Aliberti S, di Pasquale M, Zanaboni AM, et al. Stratifying risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens in hospitalized patients coming from the community with pneumonia[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2012, 54(4): 470-478. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cir840. [25] Zeng QF, Liao C, Terhune J, et al. Impacts of florfenicol on the microbiota landscape and resistome as revealed by metagenomic analysis[J]. Microbiome, 2019, 7(1): 155. DOI: 10.1186/s40168-019-0773-8. -

下载:

下载: