-

摘要:

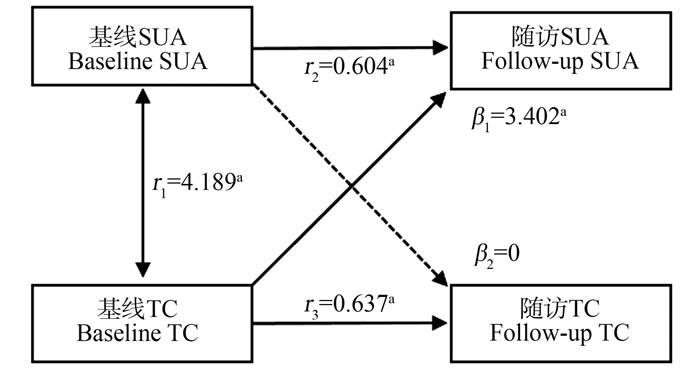

目的 研究血尿酸(serum uric acid, SUA)水平升高与血脂质之间的关系,为预防控制血脂异常和高尿酸血症提供依据。 方法 2017年4—7月在江苏省盐城市盐都区,采用多级分层随机抽样方法,对≥18岁常住居民进行基线调查,于2022年对该队列人群进行随访;采用交叉滞后模型,探讨SUA水平与血脂之间的关系,包括总胆固醇(total cholesterol, TC)、低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C)、三酰甘油(triglyceride, TG)、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C),并且针对性别进行分层分析,探究SUA水平与血脂异常的关系是否存在性别差异。 结果 共有1 347名符合条件的对象纳入研究。基线TC到随访SUA的路径系数在一般人群(β=3.402, P=0.048)和男性(β=7.214,P=0.012)中差异均有统计学意义;基线SUA到随访TC的路径系数差异无统计学意义(P=0.958)。基线TG到随访SUA的路径系数在一般人群(β=2.357, P=0.011)和男性(β=3.425,P=0.011)中差异均有统计学意义;基线SUA到随访TG的路径系数差异无统计学意义(P=0.188)。基线SUA到随访HDL-C的路径系数在一般人群(β=0.002,P<0.001)、男性(β=0.001,P<0.001)和女性(β=0.003,P<0.001)中差异均有统计学意义;基线HDL-C到随访SUA的路径系数差异无统计学意义(P=0.461)。基线SUA到随访LDL-C的路径系数在一般人群(β=0.002, P<0.001)、男性(β=0.004,P<0.001)和女性(β=0.001,P=0.015)中差异均有统计学意义;基线LDL-C到随访SUA的路径系数差异无统计学意义(P=0.436)。 结论 SUA与血脂水平之间相互影响,TC、TG水平升高可能导致SUA水平升高,从而可能导致LDL-C水平升高和HDL-C水平降低。 Abstract:Objective To study the relationship between elevated serum uric acid levels and serum lipids, and to provide evidence for the prevention and control of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia. Methods A multi-level stratified random sampling method was used to conduct a baseline survey among permanent residents aged 18 and above in Yandu District, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province from April to July 2017. And the cohort was followed up in 2022. The Cross-lag model was used to investigate the relationship between serum uric acid (SUA) level and blood lipid, including serum total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). In addition, gender stratified analysis was conducted to explore whether there were gender differences in the relationship between SUA level and dyslipidemia. Results A total of 1 347 eligible subjects were included in the study. The path coefficients from baseline TC to follow-up SUA were statistically significant in the general population (β=3.402, P=0.048) and men (β=7.214, P=0.012). The path coefficients from baseline SUA to follow-up TC were not statistically significant (P=0.958). The path coefficients from baseline TG to follow-up SUA were statistically significant in the general population (β=2.357, P=0.011) and men (β=3.425, P=0.011). The path coefficients from baseline SUA to follow-up TG were not statistically significant (P=0.188). The path coefficients from baseline SUA to follow-up HDL-C were statistically significant in the general population (β=0.002, P < 0.001), men (β=0.001, P < 0.001), and women (β=0.003, P < 0.001). The path coefficients from baseline HDL-C to follow-up SUA were not statistically significant (P=0.461). The path coefficients of baseline SUA to follow-up LDL-C were statistically significant in the general population (β=0.002, P < 0.001), men (β=0.004, P < 0.001), and women (β=0.001, P=0.015). The path coefficients from baseline LDL-C to follow-up SUA were not statistically significant (P=0.436). Conclusions Serum uric acid and lipid levels interact with each other. The increase of TC and TG levels may lead to an increase in SUA level, the increase of SUA level may lead to an increase in LDL-C level, and the increase in SUA level may lead to a decrease in HDL-C level. -

Key words:

- Cross-lagged panel model /

- Blood lipids /

- Serum uric acid /

- Cohort study /

- Causal relationship

-

表 1 交叉滞后分析中受试者的基线特征

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of subjects in cross-lagged analysis

变量Variable 合计① Total ① (n=1 347) 男性① Male ① (n=543) 女性① Female ① (n=804) Z/χ2值value P值value 年龄/岁Age/years 52.0(47.0, 60.0) 53.0(46.0, 61.0) 52.0(47.0, 60.0) 1.739 0.207 BMI/(kg·m-2) 25.3(23.2, 27.7) 25.5(23.2, 28.0) 25.3(23.2, 27.6) 0.554 0.554 SBP/mmHg-1 135.0(124.0, 148.0) 138.0(126.0, 150.8) 133.0(122.0, 147.0) 8.835 0.003 DBP/mmHg-1 85.0(77.0, 92.0) 86.0(79.0, 93.0) 83.5(76.0, 90.0) 16.429 0.001 TG/(mmol·L-1) 1.4(1.0, 2.1) 1.5(1.0, 2.2) 1.3(0.9, 1.9) 9.748 0.002 TC/(mmol·L-1) 4.8(4.2, 5.4) 4.7(4.2, 5.3) 4.9(4.2, 5.5) 8.536 0.003 HDL-C/(mmol·L-1) 1.5(1.3, 1.8) 1.5(1.2, 1.7) 1.6(1.3, 1.8) 22.259 0.001 LDL-C/(mmol·L-1) 2.6(2.2, 3.1) 2.6(2.1, 3.0) 2.6(2.2, 3.1) 0.977 0.323 FPG/(mmol·L-1) 5.7(5.3, 6.1) 5.8(5.4, 6.3) 5.6(5.3, 6.1) 16.276 0.001 HbA1c/ % 5.3(5.0, 5.6) 5.3(5.0, 5.6) 5.3(5.0, 5.6) 0.112 0.738 SUA/(mmol·L-1) 293.0(241.0, 349.0) 345.0(298.0, 398.5) 260.0(222.0, 307.0) 269.242 0.001 吸烟Smoking 289(21.5) 268(49.4) 21(2.6) 420.225 0.001 饮酒Drinking 280(20.8) 237(43.6) 43(5.3) 288.707 0.001 规律运动Regular exercise 375(27.8) 169(31.1) 206(25.6) 4.883 0.027 注:TG, 三酰甘油; TC, 总胆固醇; HDL-C, 高密度脂蛋白胆固醇; LDL-C, 低密度脂蛋白胆固醇; FPG, 空腹血糖; HbA1c, 糖化血红蛋白; SUA, 血尿酸。

①以M(P25, P75)或人数(占比/%)表示。

Note: TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; SUA, serum uric acid.

① M(P25, P75) or number of people (proportion/%). -

[1] Prabhakaran D, Anand S, Watkins D, et al. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and related disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10126): 1224-1236. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32471-6. [2] Zhang M, Deng Q, Wang LH, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and achievement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets in Chinese adults: a nationally representative survey of 163, 641 adults[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2018, 260: 196-203. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.069. [3] Filiopoulos V, Hadjiyannakos D, Vlassopoulos D. New insights into uric acid effects on the progression and prognosis of chronic kidney disease[J]. Ren Fail, 2012, 34(4): 510-520. DOI: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.653753. [4] Wei FJ, Sun N, Cai CY, et al. Associations between serum uric acid and the incidence of hypertension: a Chinese senior dynamic cohort study[J]. J Transl Med, 2016, 14(1): 110. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-016-0866-0. [5] Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, et al. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 2010, 62(2): 170-180. DOI: 10.1002/acr.20065. [6] Liang J, Jiang YT, Huang YF, et al. The comparison of dyslipidemia and serum uric acid in patients with gout and asymptomatic hyperuricemia: a cross-sectional study[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2020, 19(1): 31. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-020-1197-y. [7] Chen SH, Yang H, Chen YS, et al. Association between serum uric acid levels and dyslipidemia in Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study and further meta-analysis[J]. Medicine, 2020, 99(11): e19088. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019088. [8] Son M, Seo J, Yang S. Association between dyslipidemia and serum uric acid levels in Korean adults: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2016-2017[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(2): e0228684. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228684. [9] Wang X, Zhong S, Guo X. The associations between fasting glucose, lipids and uric acid levels strengthen with the decile of uric acid increase and differ by sex[J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2022, 32(12): 2786-2793. DOI: 10.1016/j.numecd.2022.09.004. [10] 常巍, 张雪辉, 汪洋, 等. 云南某农村高尿酸血症与血脂异常的相关性分析[J]. 昆明医科大学学报, 2018, 39(6): 124-127. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4706.2018.06.026.Chang W, Zhang XH, Wang Y, et al. The correlation analysis between hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia in rural areas, Yunnan Province[J]. Journal of Kunming Medical University, 2018, 39(6): 124-127. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4706.2018.06.026. [11] 刘璐, 马晓凡, 叶飞, 等. 乌鲁木齐市哈萨克族人群高尿酸血症与代谢性疾病的研究[J]. 职业与健康, 2018, 34(5): 634-637. DOI: 10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2018.0176.Liu L, Ma XF, Ye F, et al. Study on hyperuricemia and metabolic diseases in Kazak people in Urumqi[J]. Occup and Health, 2018, 34(5): 634-637. DOI: 10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2018.0176. [12] 周广帅, 范冰冰, 王春霞, 等. 交叉滞后路径分析在变量因果时序关系研究中的应用[J]. 中国卫生统计, 2020, 37(6): 813-817. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-3674.2020.06.004.Zhou GS, Fan BB, Wang CX, et al. Application of cross-lagged path analysis in studying temporal relationship between intercorrelated variables[J]. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 2020, 37(6): 813-817. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-3674.2020.06.004. [13] 袁空军, 余星磊, 赵创艺, 等. 高尿酸血症对老年人血脂异常患病的影响: 基于倾向性评分匹配的实证研究[J]. 中国循证医学杂志, 2022, 22(7): 785-790. DOI: 10.7507/1672-2531.202203006.Yuan KJ, Yu XL, Zhao CY, et al. Effects of hyperuricemia on the prevalence of dyslipidemia in the elderly: an empirical study based on propensity score matching[J]. Chin J Evid-Based Med, 2022, 22(7): 785-790. DOI: 10.7507/1672-2531.202203006. [14] Zhang SS, Wang Y, Cheng JS, et al. Hyperuricemia and cardiovascular disease[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2019, 25(6): 700-709. DOI: 10.2174/1381612825666190408122557. [15] Yang F, Liu MY, Qin NK, et al. Lipidomics coupled with pathway analysis characterizes serum metabolic changes in response to potassium oxonate induced hyperuricemic rats[J]. Lipids Health Dis, 2019, 18(1): 112. DOI: 10.1186/s12944-019-1054-z. [16] 孙昊, 崔静, 楚立云. 青岛某烟厂体检人群不同血脂指标与高尿酸血症关系[J]. 青岛大学学报(医学版), 2020, 56(6): 723-726. DOI: 10.11712/jms.2096-5532.2020.56.177.Sun H, Cui J, Chu LY. Relationship between different blood lipid indexes and hyperuricemia in physical examination population of a cigarette factory in Qingdao[J]. Journal of Qingdao University (Medical Sciences), 2020, 56(6): 723-726. DOI: 10.11712/jms.2096-5532.2020.56.177. [17] 朱佳妮, 齐心月, 谭杨, 等. 中老年人群高尿酸血症与糖脂代谢紊乱及膳食因素的关系研究[J]. 四川大学学报(医学版), 2016, 47(1): 68-72. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7372.2010.03.015.Zhu JN, Qi XY, Tan Y, et al. Dietary factors associated with hyperuricemia and glyeolipid metabolism disorder in middle-aged and elderly people[J]. J Sichuan Univ (Med Sci), 2016, 47(1): 68-72. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7372.2010.03.015. [18] Stelmach MJ, Wasilewska N, Wicklund-Liland LI, et al. Blood lipid profile and BMI-Z-score in adolescents with hyperuricemia[J]. Ir J Med Sci, 2015, 184(2): 463-468. DOI: 10.1007/s11845-014-1146-8. [19] Peng TC, Wang CC, Kao TW, et al. Relationship between hyperuricemia and lipid profiles in US adults[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 127596. DOI: 10.1155/2015/127596. [20] Rathmann W, Funkhouser E, Dyer AR, et al. Relations of hyperuricemia with the various components of the insulin resistance syndrome in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults[J]. Ann Epidemiol, 1998, 8(4): 250-261. DOI: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00204-4. [21] Nakagawa T, Hu HB, Zharikov S, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome[J]. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol, 2006, 290(3): F625-F631. DOI: 10.1152/ajprenal.00140.2005. [22] 宋理毅. 高尿酸血症与代谢综合征相关性的研究进展[J]. 黑龙江医学, 2019, 44(9): 1134-1135, 1138. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5775.2019.09.062.Song LY. Research progress of correlation between hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome[J]. Heilongjiang Medical Jouranl, 2019, 44(9): 1134-1135, 1138. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5775.2019.09.062. [23] Feng XJ, Yang YY, Xie HQ, et al. The association between hyperuricemia and obesity metabolic phenotypes in Chinese general population: a retrospective analysis[J]. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 773220. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2022.773220. [24] Techatraisak K, Kongkaew T. The association of hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome in Thai postmenopausal women[J]. Climacteric, 2017, 20(6): 552-557. DOI: 10.1080/13697137.2017.1369513. [25] Yu C, Zhou XL, Wang T, et al. Positive correlation between fatty liver index and hyperuricemia in hypertensive Chinese adults: a h-type hypertension registry study[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2023, 14: 1183666. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1183666. -

下载:

下载: