Association of greenness exposure and particulate matter exposure with ischemic stroke patients mortality in a cohort study

-

摘要:

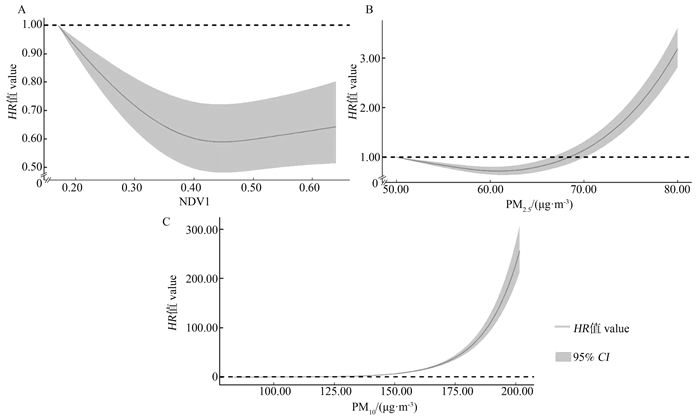

目的 基于卫星遥感数据评估的绿地暴露和颗粒物暴露与缺血性脑卒中(ischemic stroke, IS)死亡的关联。 方法 在山东5个县(区)收集2013―2019年患IS的个案病例,构建IS患者队列。根据每个患者的居住地址匹配归一化植被指数(normalized differential vegetation index, NDVI)夏季暴露值和PM2.5、PM10的年均暴露浓度。采用Cox比例风险回归模型探讨长期绿地暴露与PM2.5和PM10的联合暴露及其交互作用与IS患者死亡的关联,并且按性别、年龄和居住地进行分层分析。采用限制性立方样条函数分别评估绿地暴露、PM2.5和PM10与IS患者死亡风险的暴露-反应关系。 结果 共纳入59 084人,因IS死亡4 726人(8.00%)。分析结果显示:在评估NDVI与PM2.5和PM10的联合暴露时发现NDVI与IS患者死亡风险呈负相关。交互作用结果表明:NDVI每增加0.1个单位,IS患者的死亡风险为0.74(95% CI:0.67~0.82),PM2.5每增加10 μg/m3的IS患者的死亡风险为0.94(0.88~1.00),交互项为1.04 (1.02~1.07)。年龄、性别和居住地是影响NDVI与PM2.5和PM10的联合暴露及其交互作用与IS患者死亡关联的效应修饰因子。NDVI与IS患者死亡风险的暴露-反应关系曲线呈非线性趋势,PM2.5和PM10与IS患者死亡风险的暴露-反应关系曲线呈“U”型和“J”型。 结论 绿地暴露可能降低IS患者的死亡风险,同时进行良好的绿地规划以及降低PM2.5和PM10的暴露浓度可能进一步降低该病的死亡风险。 Abstract:Objective The interaction between greenness exposure and mortality from ischemic stroke (IS) was assessed based on satellite remote sensing data (NDVI). Methods Individual cases suffering from IS from 2013-2019 were collected in five counties in Shandong to construct a cohort of IS patients. NDVI summer exposure values and annual average exposure concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 were matched according to the residential address of each patient. Cox proportional risk models were used to explore the association between long-term greenfield exposure and combined exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 and their interactions with ischemic stroke death, and the analyses were stratified by sex, age, and residence. Restricted cubic spline functions were used to assess the dose-response relationship between greenfield exposure, PM2.5 and PM10 and the risk of death in IS patients, respectively. Results The cohort included 59 084 individuals and 4 726 (8.00%) deaths due to IS. The results of the model′s analysis showed that NDVI was negatively associated with the risk of death in patients with IS when assessing the combined exposure of NDVI with PM2.5 and PM10. The interaction results showed that the IS mortality hazard ratio (HR) for each 0.1-unit increase in NDVI was 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67-0.82), each 10 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.88-1.00), and the interaction term was 1.04 (95% CI: 1.02-1.07). Age, sex, and residence were effect modifiers influencing the association of combined exposure to NDVI with PM2.5 and PM10 and its interaction with death in IS patients. NDVI was nonlinearly associated with IS death, and PM2.5 and PM10 were associated with IS death in a "U" and "J" pattern, respectively. Conclusions Greenness exposure may reduce the risk of death from IS, while the risk of death from the disease may be further reduced by practicing good greenness planning and by reducing exposure concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10. -

图 1 NDVI、PM2.5和PM10与缺血脑卒中患者死亡风险的暴露-反应关系

NDVI: 归一化植被指数;PM2.5: 细颗粒物;PM10: 可吸入颗粒物。

Figure 1. Exposure-response relationships between NDVI, PM2.5, and PM10 and the risk of death in ischemic stroke patients

NDVI: normalized differential vegetation index; PM2.5: fine particulate matter; PM10: inhaled particulate matter.

表 1 研究对象基本特征

Table 1. Basic characteristics of research subjects

变量Variable 缺血性脑卒中患者①

Ischemic stroke patients①队列信息The cohort information 随访人数Number of follow-ups 59 084(100.00) 人时数/人年Person-hours/person-years 159 586.68 死亡人数Number of deaths 4 726(8.00) 绿地暴露Grenness Expouse 归一化植被指数Normalized differential vegetation index 0.39±0.11 空气污染/(μg·m-3) Air pollution/(μg·m-3) 细颗粒物Fine particulate matter 64.06±9.02 可吸入颗粒物Inhaled particulate matter 115.19±14.48 协变量Covariate 性别Gender 男Male 33 022(55.89) 女Female 26 062(44.11) 年龄组/岁Age group/years ≤60 17 193(29.10) >60 41 890(70.90) 居住地区Residence 城市 35 812(60.73) 农村 23 202(39.27) 县级变量County variables 人均GDP /元GDP per capita/CNY 76 126.29(61 176.29, 107 625.21) 床位数/每千人Number of beds/per 1 000 population 4.78(1.39, 10.03) 医生数/每千人Number of doctors / per 1 000 population 5.54(4.30, 15.54) 吸烟率/% Smoking prevalence / % 20.68(12.10, 21.83) 饮酒率/% Drinking rate/% 24.67(17.29, 24.67) 村级变量Village variables 人口密度/ (人·km-2) Population density/ (persons·km-2) 988.60(553.59, 4 323.03) 道路密度/(km·km-2) Road density/(km·km-2) 6.66±9.29 注:①以人数(占比/%)、x±s和M(P25, P75)表示。

Note: ① Number of people(proportion/%), x±s, M(P25, P75).表 2 长期绿地暴露和颗粒物暴露(PM2.5和PM10)的独立效应和联合暴露与缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的关联

Table 2. Association of independent and joint effects of long-term greenness exposure and particulate matter exposure (PM2.5 and PM10) with ischemic stroke mortality

主模型和亚组分析

Main model and subgroup analysis模型1 Model 1

NDVI模型2 Model 2

PM2.5模型3 Model 3

PM10模型4 Model 4 模型5 Model 5 NDVI PM2.5 NDVI PM10 主模型Main model 0.96(0.93~0.98) 1.11(1.09~1.13) 1.06 (1.04~1.08) 0.97(0.94~0.98) 1.06(1.04~1.07) 0.97(0.94~0.99) 1.11 (1.09~1.13) 亚组分析Subgroup analysis 性别Gender 男Male 0.95 (0.91~0.99) 1.01(1.08~1.13) 1.05 (1.03~1.07) 0.96(0.92~1.00) 1.10(1.07~1.13) 0.96(0.92~0.99) 1.05(1.03~1.07) 女Female 0.97 (0.93~1.01) 1.12(1.09~1.15) 1.07 (1.05~1.20) 0.98(0.94~1.03) 1.12(1.09~1.15) 0.98(0.94~1.03) 1.07(1.05~1.09) 年龄组/岁Age group /years 40~60 0.98(0.89~1.08) 1.11(1.05~1.18) 1.06 (1.01~1.12) 0.99(0.90~1.09) 1.12(1.06~1.19) 0.99(0.90~1.09) 1.06(1.01~1.12) >60~70 0.92 (0.86~0.98) 1.07(1.03~1.12) 1.04 (1.00~1.07) 0.92(0.86~0.99) 1.07(1.02~1.11) 0.92(0.86~0.98) 1.03(0.99~1.07) >70~80 0.97 (0.92~1.03) 1.12(1.08~1.15) 1.07 (1.04~1.20) 0.99(0.93~1.04) 1.12(1.08~1.15) 0.99(0.93~1.04) 1.07(1.04~1.09) >80~90 0.95(0.90~1.00) 1.12(1.08~1.15) 1.06 (1.03~1.09) 0.97(0.91~1.02) 1.12(1.08~1.15) 0.96(0.91~1.02) 1.06(1.03~1.09) >90 1.03(0.87~1.22) 1.17(1.81~1.28) 1.12(1.04~1.21) 1.05(0.90~1.24) 1.18(1.09~1.28) 1.56(0.90~1.24) 1.13(1.05~1.21) 居住地Residence 城市Urban 1.02(0.97~1.07) 1.07(1.04~1.10) 1.03 (1.01~1.05) 1.03(0.97~1.08) 1.07(1.04~1.10) 1.03(0.97~1.08) 1.03(1.01~1.05) 农村Rural 0.89(0.86~0.93) 1.15(0.12~1.18) 1.10 (1.07~1.12) 0.91(0.87~0.95) 1.14(1.12~1.72) 0.91(0.87~0.94) 1.09(1.07~1.12) 注:NDVI, 归一化植被指数;PM2.5, 细颗粒物;PM10, 可吸入颗粒物。

所有模型都对年龄、性别、居住地、人口密度、床位数、受初等教育人数、人均GDP、道路密度、吸烟率和饮酒率进行了调整。模型1评估了NDVI每增加0.1个单位对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的影响;模型2评估了PM2.5每增加10 μg/m-3对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的影响;模型3评估了PM10每增加10 μg/m-3对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的影响;模型4评估了NDVI每增加0.1个单位和PM2.5每增加10 μg/m-3对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的影响;模型5评估了NDVI每增加0.1个单位和PM10每增加10 μg/m-3对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的影响。

Note: NDVI, normalized differential vegetation index; PM2.5, fine particulate matter; PM10, inhaled particulate matter.

All models were adjusted for age, sex, place of residence, population density, number of beds, number of people with primary education, GDP per capita, road density, smoking prevalence, and alcohol consumption. Model 1 assessed the effect of each 0.1-unit increase in NDVI on deaths in ischemic stroke patients; model 2 assessed the effect of each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM2.5 on deaths in ischemic stroke patients; model 3 assessed the effect of each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM10 on deaths in ischemic stroke patients; and model 4 assessed the effect of each 0.1-unit increase in NDVI and each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM2.5 on deaths in ischemic stroke patients. per 10 μg/m-3 increase in NDVI and PM2.5 per 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM2.5 on death in patients with ischemic stroke; and Model 5 assessed the effect of each 0.1 unit increase in NDVI and each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM10 on death in patients with ischemic stroke.表 3 长期绿地暴露和颗粒物暴露(PM2.5和PM10)之间的交互作用与缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的关联

Table 3. Association between long-term greenness exposure and particulate matter exposure (PM2.5, PM10) and ischemic stroke mortality

主模型和亚组分析

Main model and subgroup analysis模型1 Model 1 模型2 Model 2 NDVI PM2.5 交互项

InteractionP交互值

Pinteraction valueNDVI PM10 交互项

InteractionP交互值

Pinteraction value主模型Main model 0.74(0.67~0.82) 0.94(0.88~1.00) 1.04(1.02~1.07) <0.001 0.75(0.66~0.82) 0.97(0.93~1.01) 1.03(1.01~1.04) <0.001 亚组分析Subgroup analysis 性别Gender 男Male 0.74(0.67~0.81) 0.93(0.88~1.00) 1.06(1.03~1.08) 0.001 0.72(0.60~0.85) 0.95(0.89~1.01) 1.03(1.01~1.05) 0.001 女Female 0.78(0.68~0.91) 0.97(0.88~1.06) 1.03(1.00~1.06) 0.001 0.80(0.67~0.96) 1.00(0.93~1.07) 1.02(0.99~1.04) 0.114 年龄组/岁Age group/years 40~60 0.82(0.59~1.15) 0.99(0.81~1.22) 1.00(0.94~1.07) 0.146 0.82(0.55~1.24) 0.99(0.86~1.15) 1.00(0.95~1.05) 0.352 >60~70 0.80(0.56~1.11) 0.86(0.73~1.01) 1.05(1.00~1.11) 0.005 0.71(0.52~0.97) 0.94(0.84~1.05) 1.01(0.98~1.06) 0.437 >70~80 0.83(0.69~0.99) 1.00(0.90~1.12) 1.04(1.00~1.08) 0.044 0.83(0.67~1.03) 1.00(0.93~1.09) 1.02(0.99~1.05) 0.112 >80~90 0.66(0.57~0.81) 0.88(0.80~0.98) 1.07(1.04~1.10) 0.001 0.64(0.52~0.79) 0.92(0.85~0.99) 1.05(1.01~1.10) 0.001 >90 1.37(0.84~2.25) 1.39(1.03~1.80) 0.96(0.88~1.05) 0.256 1.49(0.82~2.70) 1.27(1.03~1.57) 0.97(0.90~1.04) 0.232 居住地Residence 城市Urban 0.98(0.84~1.14) 1.04(0.97~1.13) 1.02(0.99~1.05) 0.190 1.13(0.93~1.38) 1.06(1.00~1.12) 1.00(0.97~1.02) 0.639 农村Rural 0.53(0.45~0.63) 0.77(0.68~0.88) 1.07(1.02~1.12) 0.003 0.43(0.34~0.54) 0.79(0.71~0.88) 1.06(1.02~1.10) 0.002 注:1. NDVI, 归一化植被指数;PM2.5, 细颗粒物;PM10, 可吸入颗粒物。

2. 所有模型都对年龄、性别、居住地、人口密度、床位数、受初等教育人数、人均GDP、道路密度、吸烟率和饮酒率进行了调整。模型1评估了NDVI每增加0.1个单位、PM2.5每增加10 μg/m-3、NDVI(每增加0.1个单位)与PM2.5(每增加10 μg/m-3)的乘积项对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡所产生的交互作用;模型2评估了NDVI每增加0.1个单位、PM10每增加10 μg/m-3、NDVI(每增加0.1个单位)与PM10(每增加10 μg/m-3)的乘积项对缺血性脑卒中患者死亡的所产生的交互作用。

Note: 1. NDVI, normalized differential vegetation index; PM2.5, fine particulate matter; PM10, inhaled particulate matter.

2. All models were adjusted for age, sex, place of residence, population density, number of beds, number of people with primary education, GDP per capita, road density, smoking prevalence and alcohol consumption. Model 1 assessed the interaction effect of each 0.1 unit increase in NDVI, each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM2.5, and the product term of NDVI (for each 0.1 unit increase) and PM2.5 (for each 10 μg/m-3 increase) on deaths of patients with ischemic stroke; and Model 2 assessed the interaction effect of each 0.1 unit increase in NDVI, each 10 μg/m-3 increase in PM10, Model 2 assessed the interaction between the product of NDVI (per 0.1 unit increase) and PM10 (per 10 μg/m-3 increase) on death in ischemic stroke patients. -

[1] Ding QQ, Liu SW, Yao YD, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of ischemic stroke, 1990-2019[J]. Neurology, 2022, 98(3): e279-e290. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013115. [2] Ji JS, Zhu AN, Lv YB, et al. Interaction between residential greenness and air pollution mortality: analysis of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey[J]. Lancet Planet Health, 2020, 4(3): e107-e115. DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30027-9. [3] Bo YC, Zhu YJ, Zhang XA, et al. Spatiotemporal trends of stroke burden attributable to ambient PM2.5 in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019[J]. Neurology, 2023, 101(7): e764-e776. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000207503. [4] World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [5] Liu XX, Ma XL, Huang WZ, et al. Green space and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis[J]. Environ Pollut, 2022, 301: 118990. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.118990. [6] Wang D, Lau KKL, Yu R, et al. Neighbouring green space and mortality in community-dwelling elderly Hong Kong Chinese: a cohort study[J]. BMJ Open, 2017, 7(7): e015794. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015794. [7] Diener A, Mudu P. How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces' mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective - with implications for urban planning[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2021, 796: 148605. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148605. [8] Wei J, Li ZQ, Lyapustin A, et al. Reconstructing 1-km-resolution high-quality PM2.5 data records from 2000 to 2018 in China: spatiotemporal variations and policy implications[J]. Remote Sens Environ, 2021, 252: 112136. DOI: 10.1016/j.rse.2020.112136. [9] Leng H, Li SY, Yan SC, et al. Exploring the relationship between green space in a neighbourhood and cardiovascular health in the winter city of China: a study using a health survey for Harbin[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(2): 513. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17020513. [10] Liu T, Cai B, Peng WJ, et al. Association of neighborhood greenness exposure with cardiovascular diseases and biomarkers[J]. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2021, 234: 113738. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113738. [11] Avellaneda-Gómez C, Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Olmos S, et al. Air pollution and surrounding greenness in relation to ischemic stroke: a population-based cohort study[J]. Environ Int, 2022, 161: 107147. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107147. [12] Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Avellaneda-Gómez C, Dadvand P, et al. Association of residential air pollution, noise, and greenspace with initial ischemic stroke severity[J]. Environ Res, 2019, 179(Pt A): 108725. DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108725. [13] Liao NS, Van Den Eeden SK, Sidney S, et al. Joint associations between neighborhood walkability, greenness, and particulate air pollution on cardiovascular mortality among adults with a history of stroke or acute myocardial infarction[J]. Environ Epidemiol, 2022, 6(2): e200. DOI: 10.1097/EE9.0000000000000200. [14] Vienneau D, de Hoogh K, Faeh D, et al. More than clean air and tranquillity: residential green is independently associated with decreasing mortality[J]. Environ Int, 2017, 108: 176-184. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.012. [15] Roscoe C, MacKay C, Gulliver J, et al. Associations of private residential gardens versus other greenspace types with cardiovascular and respiratory disease mortality: Observational evidence from UK Biobank[J]. Environ Int, 2022, 167: 107427. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107427. [16] Bauwelinck M, Casas L, Nawrot TS, et al. Residing in urban areas with higher green space is associated with lower mortality risk: a census-based cohort study with ten years of follow-up[J]. Environ Int, 2021, 148: 106365. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106365. [17] Ji JS, Zhu AN, Bai C, et al. Residential greenness and mortality in oldest-old women and men in China: a longitudinal cohort study[J]. Lancet Planet Health, 2019, 3(1): e17-e25. DOI: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30264-X. [18] Seo S, Choi S, Kim K, et al. Association between urban green space and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a longitudinal study in seven Korean metropolitan areas[J]. Environ Int, 2019, 125: 51-57. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.038. [19] Yeager R, Riggs DW, DeJarnett N, et al. Association between residential greenness and cardiovascular disease risk[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018, 7(24): e009117. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009117. [20] Potter JD, Brooks C, Donovan G, et al. A perspective on green, blue, and grey spaces, biodiversity, microbiota, and human health[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2023, 892: 164772. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164772. -

下载:

下载: