Urate-lowering drugs and colorectal cancer risk: an observational study and Mendelian randomization analysis

-

摘要:

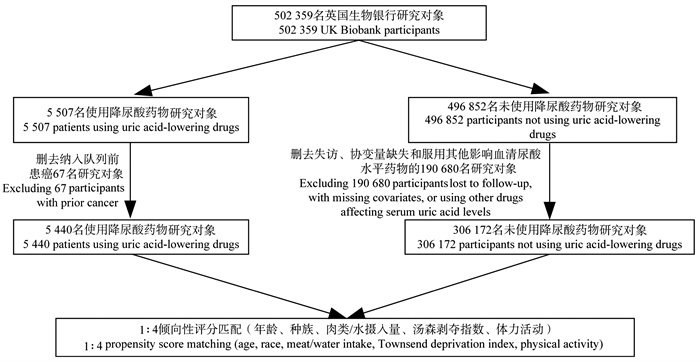

目的 评估降尿酸药物及其药物靶点与结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC)发生的关联。 方法 基于英国生物银行2006―2010年的数据(申请号:62663)进行前瞻性队列研究,采用倾向性评分匹配和Cox比例风险回归模型探讨降尿酸药物的使用对CRC发生风险的影响。同时采用孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization, MR)方法,以降尿酸药物靶基因的表达数量性状位点作为工具变量,分析3类降尿酸药物与CRC发生的关联性。 结果 研究共纳入5 440名降尿酸药物使用者,年龄中位数为52.0岁,92.1%为男性,中位随访12.75年,共发生117例CRC。Cox比例风险回归模型显示,降尿酸药物使用者的CRC发生风险比未使用降尿酸药物者降低了20.2%(HR=0.798, 95% CI: 0.652~0.976, P=0.029)。MR分析表明,以溶质载体家族22成员12(solute carrier family 22 member 12, SLC22A12)作为治疗靶点可以降低CRC的发生风险(OR=0.834, 95% CI: 0.734~0.949, P=0.006)。 结论 降尿酸药物和SLC22A12靶向的促尿酸排泄剂与CRC发生相关,为解释降尿酸药物与CRC的关联提供了可能的线索。 Abstract:Objective Assessing the association between uric acid-lowering drugs and their targets with the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC). Methods Based on data from the UK Biobank from 2006 to 2010 (application No: 62663), a prospective cohort study was conducted to explore the impact of uric acid-lowering drug use on the risk of CRC using propensity score matching and Cox proportional hazards model. Additionally, Mendelian randomization (MR) was employed, utilizing expression quantitative trait loci of genes targeted by uric acid-lowering drugs as instrumental variables, to analyze the associations between three types of uric acid-lowering drugs and the occurrence of CRC. Results The study included a total of 5 440 users of uric acid-lowering drugs, with a median age of 52.0 years, of whom 92.1% were male. The median follow-up period was 12.75 years, during which 117 cases of CRC were reported. The Cox proportional hazards model showed that the risk of CRC in users of uric acid-lowering drugs was reduced by 20.2% compared to non-users (HR=0.798, 95% CI: 0.652-0.976, P=0.029). MR analysis suggested that targeting solute carrier family 22 member 12 (SLC22A12) may reduce the risk of CRC (OR=0.834, 95% CI: 0.734-0.949, P=0.006). Conclusions Uric acid-lowering drugs and SLC22A12-targeted uricosuric agents are associated with the occurrence of CRC, providing possible insights into explaining the relationship between uric acid-lowering drugs and CRC. -

Key words:

- Urate-lowering drugs /

- Colorectal cancer /

- Mendelian randomization /

- Prospective cohort

-

图 2 留一法分析评估SLC22A12单个SNP对孟德尔随机化结果稳定性的影响

SLC22A12:溶质载体家族22成员12; SNP:单核苷酸多态性。

Figure 2. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis evaluating the impact of individual SNPs in SLC22A12 on the stability of Mendelian randomization results

SLC22A12: solute carrier family 22 member 12; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism.

表 1 人口学特征的变量赋值表

Table 1. Assignment of variables for demographic characteristics

变量Characteristic 赋值Code 性别Gender 0=女性,1=男性0=female, 1=male 种族Ethnic 0=非白种人,1=白种人0=non-white, 1=white 吸烟Smoking 0=当前(包括每日规律吸烟者和偶尔吸烟者)和既往(曾经规律或偶尔吸烟但目前已戒烟)吸烟,1=从未吸烟(终生吸烟量<100支)

0=current/former smoker (regular or occasional, including quit), 1=never smoker (<100 lifetime cigarettes)饮酒频率Alcohol intake frequency 0=当前(过去1年中每周饮用≥1标准杯酒精饮品)和既往(曾有规律或偶尔饮酒史,但已持续戒酒≥12个月)饮酒者,1=从不饮酒者(终生累计饮酒量<12标准杯酒精饮品)

0=current/former drinker (≥1 drink/week in past year or history with ≥12-month abstinence), 1=lifetime abstainer (<12 total standard drinks)肉类摄入量Meat intake 0=少量(每周≤1次),1=中等(每周2~4次),2=经常(每周≥5次) 0=low (≤1/week), 1=moderate (2-4/week), 2=high (≥5/week) 学历Qualifications 0=大学学历,1=其他学历0=college degree, 1=other 表 2 降尿酸药物使用与结直肠癌发病风险的多因素Cox比例风险回归分析结果

Table 2. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of uric acid-lowering drug use and the risk of colorectal cancer

变量Characteristic 模型1 Model 1 模型2 Model 2 模型3 Model 3 HR值value(95% CI) P值value HR值value(95% CI) P值value HR值value(95% CI) P值value 降尿酸药物使用Uric acid-lowering drug use 0.829(0.679~1.012) 0.065 0.811(0.662~0.994) 0.042 0.798(0.652~0.976) 0.029 年龄/岁Age/years 1.069(1.055~1.084) <0.01 1.067(1.053~1.080) <0.01 1.066(1.052~1.080) <0.01 性别Gender 1.191(0.816~1.739) 0.366 1.196(0.818~1.749) 0.357 1.281(0.872~1.882) 0.207 种族Ethnic 1.366(0.823~2.267) 0.227 1.391(0.838~2.308) 0.202 1.382(0.832~2.294) 0.211 BMI/(kg·m-2) 0.966(0.935~0.999) 0.042 0.964(0.933~0.996) 0.030 0.966(0.935~0.998) 0.041 腰围Waist circumference/cm 1.021(1.008~1.035) 0.002 1.021(1.008~1.035) 0.002 1.021(1.008~1.035) 0.001 吸烟Smoking 0.907(0.775~1.061) 0.222 0.914(0.780~1.071) 0.263 0.912(0.779~1.068) 0.250 饮酒频率Alcohol intake frequency 0.993(0.598~1.648) 0.978 0.978(0.590~1.622) 0.933 0.970(0.585~1.610) 0.908 学历Qualifications 0.880(0.745~1.041) 0.136 0.877(0.742~1.037) 0.125 0.874(0.739~1.033) 0.115 汤森剥夺指数Townsend deprivation index 0.995(0.970~1.020) 0.674 0.993(0.968~1.019) 0.593 0.993(0.968~1.019) 0.574 白蛋白Albumin/(g·L-1) 0.983(0.955~1.012) 0.257 0.985(0.957~1.014) 0.315 总胆固醇Total cholesterol/(mmol·L-1) 0.952(0.889~1.020) 0.165 0.958(0.894~1.026) 0.222 C反应蛋白C-reactive protein/(mg·L-1) 1.009(0.996~1.023) 0.164 1.011(0.997~1.025) 0.114 血清尿酸Serum uric acid/(μmol·L-1) 0.999(0.998~1.000) 0.013 注:模型1,纳入降尿酸药物使用、年龄、性别、种族、BMI、腰围、吸烟、饮酒频率、学历和汤森剥夺指数;模型2,纳入降尿酸药物使用、年龄、性别、种族、BMI、腰围、吸烟、饮酒频率、学历、汤森剥夺指数、白蛋白、总胆固醇和C反应蛋白;模型3,降尿酸药物使用、年龄、性别、种族、BMI、腰围、吸烟、饮酒频率、学历、汤森剥夺指数、白蛋白、总胆固醇、C反应蛋白和血清尿酸。

Note: Model 1 includes uric acid-lowering drug use, age, gender, ethnic, BMI, waist circumference, smoking, alcohol intake frequency, qualifications, and Townsend deprivation index; Model 2 includes uric acid-lowering drug use, age, gender, ethnic, BMI, waist circumference, smoking, alcohol intake frequency, qualifications, Townsend deprivation index, albumin, total cholesterol, and C-reactive protein; Model 3 includes uric acid-lowering drug use, age, gender, ethnic, BMI, waist circumference, smoking, alcohol intake frequency, qualifications, Townsend deprivation index, albumin, total cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and serum uric acid.表 3 XDH、SLC22A12和PNP靶基因对结直肠癌的效应

Table 3. Effects of XDH, SLC22A12 and PNP target genes on colorectal cancer

药物靶点基因

Drug target gene疾病结局

Disease outcome方法

MethodsSNP数量

Number of SNPsOR值value(95% CI) P值value SLC22A12 结直肠癌Colorectal cancer 逆方差加权法Inverse variance weighting 77 0.834(0.734~0.949) 0.006 加权中位数Weighted median 77 0.812(0.675~0.977) 0.027 加权模式Weighted mode 77 0.816(0.689~0.966) 0.021 PNP 结直肠癌Colorectal cancer 逆方差加权法Inverse variance weighting 37 0.566(0.284~1.128) 0.106 加权中位数Weighted median 37 0.595(0.245~1.445) 0.251 加权模式Weighted mode 37 0.556(0.191~1.613) 0.287 XDH 结直肠癌Colorectal cancer 逆方差加权法Inverse variance weighting 31 0.628(0.346~1.141) 0.127 加权中位数Weighted median 31 0.533(0.205~1.385) 0.197 加权模式Weighted mode 31 0.432(0.122~1.527) 0.203 注:XDH,黄嘌呤脱氢酶;SLC22A12,溶质载体家族22成员12;PNP,嘌呤核苷酸磷酸化酶;SNP,单核苷酸多态性。

Note: XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase; SLC22A12, solute carrier family 22 Member 12; PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism. -

[1] Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2024, 74(3): 229-263. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21834. [2] Abedizadeh R, Majidi F, Khorasani HR, et al. Colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of carcinogenesis, diagnosis, and novel strategies for classified treatments[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2024, 43(2): 729-753. DOI: 10.1007/s10555-023-10158-3. [3] Mi SY, Gong L, Sui ZQ. Friend or foe? an unrecognized role of uric acid in cancer development and the potential anticancer effects of uric acid-lowering drugs[J]. J Cancer, 2020, 11(17): 5236-5244. DOI: 10.7150/jca.46200. [4] Mao LN, Guo C, Zheng S. Elevated urinary 8-oxo-7, 8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine and serum uric acid are associated with progression and are prognostic factors of colorectal cancer[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2018, 11: 5895-5902. DOI: 10.2147/OTT.S175112. [5] Li WQ, Liu T, Siyin ST, et al. The relationship between serum uric acid and colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study[J]. Sci Rep, 2022, 12(1): 16677. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-20357-7. [6] Wei F, Nian Q, Zhao MY, et al. Natural products and mitochondrial allies in colorectal cancer therapy[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2023, 167: 115473. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115473. [7] Fu Q, Liao HN, Li ZH, et al. Preventive effects of 13 different drugs on colorectal cancer: a network Meta-analysis[J]. Arch Med Sci, 2023, 19(5): 1428-1445. DOI: 10.5114/aoms/167480. [8] Zhang HP. Pros and cons of mendelian randomization[J]. Fertil Steril, 2023, 119(6): 913-916. DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.03.029. [9] Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV, et al. Mendelian randomization[J]. Nat Rev Meth Primers, 2022, 2: 6. DOI: 10.1038/s43586-021-00092-5. [10] Wang LJ, Mesa-Eguiagaray I, Campbell H, et al. A phenome-wide association and factorial Mendelian randomization study on the repurposing of uric acid-lowering drugs for cardiovascular outcomes[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2024, 39(8): 869-880. DOI: 10.1007/s10654-024-01138-0. [11] Leung N, Yip K, Pillinger MH, et al. Lowering and raising serum urate levels: off-label effects of commonly used medications[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2022, 97(7): 1345-1362. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.02.027. [12] Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Cincione RI, et al. Clinical effects of xanthine oxidase inhibitors in hyperuricemic patients[J]. Med Princ Pract, 2021, 30(2): 122-130. DOI: 10.1159/000512178. [13] Fujita K, Isozumi N, Zhu QN, et al. Unique binding sites of uricosuric agent dotinurad for selective inhibition of renal uric acid reabsorptive transporter URAT1[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2024, 390(1): 99-107. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.124.002096. [14] Lin SQ, Wu S, Zhao W, et al. TargetGene: a comprehensive database of cell-type-specific target genes for genetic variants[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2024, 52(D1): D1072-D1081. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkad901. [15] Pan HX, Liu ZH, Ma JH, et al. Genome-wide association study using whole-genome sequencing identifies risk loci for Parkinson's disease in Chinese population[J]. NPJ Parkinsons Dis, 2023, 9(1): 22. DOI: 10.1038/s41531-023-00456-6. [16] Zhou SR, Butler-Laporte G, Nakanishi T, et al. A Neanderthal OAS1 isoform protects individuals of European ancestry against COVID-19 susceptibility and severity[J]. Nat Med, 2021, 27(4): 659-667. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-021-01281-1. [17] Liu YN, Chen W, Yang RQ, et al. Effect of serum uric acid and gout on the incidence of colorectal cancer: a Meta-analysis[J]. Am J Med Sci, 2024, 367(2): 119-127. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjms.2023.11.013. [18] Alam S, Doherty E, Ortega-Prieto P, et al. Membrane transporters in cell physiology, cancer metabolism and drug response[J]. Dis Model Mech, 2023, 16(11): dmm050404. DOI: 10.1242/dmm.050404. [19] Qu Z, Wu KL, Qiu HT, et al. Genetic association between SLC22A12 variants and susceptibility to hyperuricemia: a Meta-analysis[J]. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers, 2022, 26(2): 81-95. DOI: 10.1089/gtmb.2021.0175. [20] Wang L, Ye JP. Commentary: Gut microbiota reduce the risk of hyperuricemia and gout in the human body[J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2024, 14(1): 433-435. DOI: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.11.013. [21] Sutkowy P, Czeleń P. Redox balance in cancer in the context of tumor prevention and treatment[J]. Biomedicines, 2025, 13(5): 1149. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines13051149. [22] Li HL, Zhang CJ, Zhang H, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase promotes the progression of colitis-associated colorectal cancer by causing DNA damage and mediating macrophage M1 polarization[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2021, 906: 174270. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174270. [23] Copur S, Demiray A, Kanbay M. Uric acid in metabolic syndrome: does uric acid have a definitive role?[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2022, 103: 4-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.04.022. [24] Allegrini S, Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R, et al. The good, the bad and the new about uric acid in cancer[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2022, 14(19): 4959. DOI: 10.3390/cancers14194959. [25] Cabǎu G, Crisan TO, Klück V, et al. Urate-induced immune programming: consequences for gouty arthritis and hyperuricemia[J]. Immunol Rev, 2020, 294(1): 92-105. DOI: 10.1111/imr.12833. -

下载:

下载: